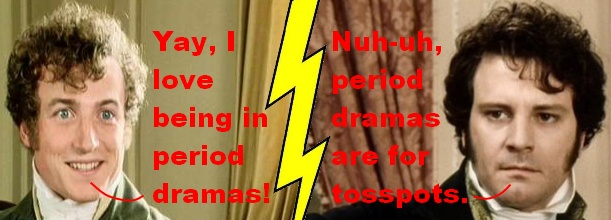

Friday Face/Off: Period films

Alice (Has a ‘thing’ for breeches and swords. Nothing Freudian about that at all):

What’s not to like? Dashing heroes, dastardly villains, gutsy heroines and acid-tongue dowagers prancing around the English countryside putting their stiff upper lips to good use and repressing every sexual urge. It’s the entire English character distilled into feature-length wonderfulness. And even the staunchest commie couldn’t deny a twinge of desire to reside in one of the beautiful, beautiful mansions that the characters lounge around in so artfully.

Morals in these films are so delightfully simple and you know that, the occasional Charlotte Lucas aside, everyone ends up with the partner they deserve – like for like. You can sit back and enjoy the sumptuous costumes and backdrops safe in the knowledge that all that tortured yearning and those silly little money worries will sort themselves out and you (sorry, Elizabeth) will marry her Darcy and move into Pemberley. Part of the huge appeal of these films is the escapism; you know you’re not going to come away with an all-new understanding of the human condition but that is beside the point. That said, Austen’s novels did deal with important issues of the day, both feminist and political. You don’t get that in your average action film.

Cherise (comes out in a nasty rash at the very sight of a corset):

If the period film is the quintessence of escapism, I’d prefer to suffer through the banality that is the real world than be stuck in an era of stilted, sexually anorexic insipidity. As far as championing the cause of feminism (which is really just the sublimated projection of penis-envy, and penises are generally pretty useless in Jane Austen’s ranting narratives) the period film does nothing to subvert the fact that the hard-up heroines will give up everything and succumb to male subjugation, just for a decent shag. It’s all hypocrisy and blasted LIES, I tell you.

Alice:

I’d succumb to Mr Knightley for a shag… But that aside, most of Austen’s heroines were way ahead of their time; Elizabeth challenging the authority of her father, turning down millionaire Darcy (the first time round) because she doesn’t love him. Marriage for the upper- and middle-classes was meant to be a business contract, this modern fancy of love a laughable idea. For Austen to acknowledge that women shouldn’t be satisfied with just a comfortable living and churning out the babies, but should want happiness aswell, it was at least a nod in the direction of feminism. It wasn’t her fault that no alternatives existed outside of wife or spinster.

Cherise:

It’s all so terribly tragic, then, that the period FILM didn’t communicate much of the actual novels’ homespun “philosophy” to which you are so endeared. And anyway, even if they did, no one would care, because that was all so 300 YEARS AGO.

Here’s a handkerchief to wipe up that schmaltz.

Alice:

Fine, fine, fine. We’ll agree to disagree. But I sometimes I’m inclined think that people who claim to hate period dramas are just pseudo-intellectuals who can’t see the history for the bonnets (or something). And there’s nothing wrong with enjoying a bit of uncomplicated, witty romance in corsets – just please don’t try and apply it to real life. Whoever wrote ‘Jane Austen’s Guide to Dating’ should be dragged backwards through the streets of Bath by a chariot-driving Germaine Greer…

Recent Comments