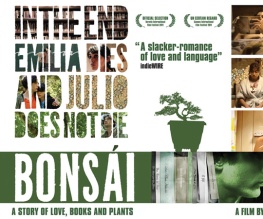

Bonsái

There’s a central motif running through Bonsái. No, it’s not tiny Japanese trees (well, actually it’s that as well). It’s Proust. You remember that guy. French, wrote a lot of dense stuff about dunking biscuits in tea. At Bonsái‘s opening, our protagonist Julio (Diego Noguera) is attempting to get through the first volume of Proust’s In Search Of Lost Time and ends up falling asleep on a sun-drenched beach, waking up later to discover a perfect white outline of said book burnt onto his chest. And really, this moment works as a metaphor for the film itself (yes, I’m going there) with Julio’s unfortunate sunburn acting as an emblem for Bonsái‘s on-the-nose literariness. Because essentially, this is a film almost entirely about literature and the process of writing. And while that makes for an interesting concept, its translation to screen is a little awkward.

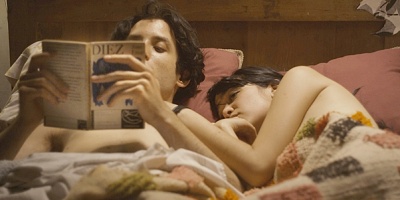

Julio is a loner student who randomly sleeps with the gloomy Emilia (Nathalia Galgani) one night. Flash forward ten years and Julio is now a loner writer who has just received a commission to type up an established author’s latest novel. In place of the absent Emilia is neighbour Blanca (Trinidad González) whom Julio pops round to for food, sex and idle conversation. When Julio’s job falls through, he decides to write his own novel, passing it off to Blanca as the other author’s work and employing her assistance in typing out the manuscript. The novel is an account of Julio’s doomed love affair with the lost Emilia and as he moves toward its completion, we flash back and forward in time, charting the events that led Julio to this point.

The most intriguing parts of Bonsái deal with Julio’s obsessive desire to get his own life down on paper, in the hope that he will find some kind of resolution, or even rewrite the mistakes of the past. The older Julio, for instance, buys and obsessively takes care of his own bonsai tree in an attempt to make up for a misjudged gesture in the past where he bought a little plant for Emilia that came to represent their floundering relationship. In the film’s most interesting and deftly handled scene, Blanca – having typed up a passage recounting Julio and Emilia’s first meeting – sheds light on what really went on between the two in that moment, much to Julio’s surprise. It’s a concept that will appeal to writers – the idea that a text can contain more meaning its author can possibly be aware of.

But ultimately, Bonsái‘s characters – however interesting they might be as literary figures – simply fail to come to life on screen. The romantic scenes are a little cold, made even more so by touches of indie quirkiness that only serve to heighten the stilted, artificial feel. Perhaps this is Jiménez’s intention; to depict figures who have been so rigorously rewritten to fit the pages of a novel that the life has leached out of them. Maybe we are intended to despair that – despite our best efforts – a lost love affair can never be recaptured through the pages of a novel.

But the plain fact is that you are left with characters who feel so distant they are almost reduced to ciphers, blankly channelling words that often fail in themselves – Julio and Emilia are frequently left chanting the words “blah, blah, blah” in place of real dialogue. These are figures who resemble people who were once real and in love, but have been lost in time, transfigured into cardboard cutouts. And while that’s a fascinating concept, it doesn’t work on the big screen. It’s a shame, but there’s something so inherently un-filmic about the subject matter that you almost wonder why Jiménez bothered at all.

Recent Comments