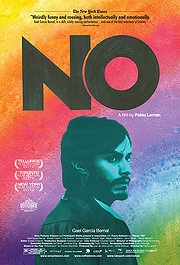

No

How do you conduct an election? By presenting policies in a clear and even-handed manner, ensuring that all sides get an equal airing in the media, and that no favouritism or bias infects proceedings. All of this should play some small part in ensuring that voters go to polls with a clear idea of who and what they’re voting for, having not been coerced or bullied into thinking a certain way. In the end, it’s all in aid of preserving that most precious commodity of civilization: democracy. Of course, that’s all complete bollocks. The public don’t know what’s best for themselves, are largely uneducated in matters of state and worst of all have little interest in exercising their right to make a difference, however small. They need catchy music, bright colours and smiling faces to tell them what to do. Elections are fought with money, by pouring huge funds into advertising in the hopes that bottomless muck-raking will cause a beleaguered public to relent. Rarely is political advertising an edifying sight, but Pablo Larrain’s account of the ‘No’ campaign that ultimately dethroned the despotic Pinochet is a breath of fresh air in an age when winning ugly is the only way to succeed in politics. Without overlooking some of the questionable ethics that went into the enormously successful ‘No’ ad campaign, Larrain’s film is a memoriam to the dubious power of positive thinking, and a form of un-ironic advertising that today seems almost quaint.

Under pressure from the US, in 1988 General Augusto Pinochet called for a referendum on his presidency. His regime, characterised by a flagrant disregard for human rights, widespread imprisonment and a chilling preponderance of those known simply as ‘the disappeared’, was to be put on trial in a very public way. In the wake of current clashes across the Arab world dethroning numerous tyrants, the 1988 Chilean national plebiscite vote appears an altogether less forceful manner of voicing public opinion. No documents a society in thrall to encroaching western values, and is as much a satire on the future secured by ousting Pinochet as it is a solemn remembrance of how hard Chile had to fight to make its opposing voices heard.

Playing hotshot ad exec René Saavedra, Gael García Bernal at last ends a run of films ill-suited to his particular charms. Perfectly cast, his boyish enthusiasm and impish cheek help illuminate the ‘No’ campaign for what it truly was: incredibly slick, pandering, wilfully evasive and utterly intoxicating. Under Saavedra’s guidance, and to the chagrin of many forming the coalition whose fate lay in his hands, the ‘No’ campaign took its cue from pop music, soft drinks and the very American promise of instant happiness. Don Draper would be proud. The adverts produced look positively antiquated when seen in Larrain’s film, but the knowing humour that underpins its gradual snowball effect in the Chilean consciousness adjudges it the necessary mix of political compromise and ethical sacrifice required to win over the masses. No isn’t a mere celebration of Chile’s freedom, but a quietly prodding account of how it exchanged one form of oppression for another, less tangible overlord. Namely, the invisible cosh of advertising.

Taking control of the project, Saavedra’s adverts are a mixture of jingles, iconography and childishly ebullient sentiments well-versed in the vagueness of a political promise. Deliberately binning images of police clashes, poverty and essentially any reminders of the bad times hoping to be left behind, what emerges is a kind of monstrosity that wouldn’t seem out of place in Pepsi’s hands. It’s winning ugly, to be sure, but remains a far cry from some of the breathtaking potshots taken in last year’s Obama-Romney slugfest. Larrain acknowledges the necessity of it, and beyond that is well aware that the language of advertising can be used to sell anything, be it teeth-rotting fizz or a nation’s future.

Shooting on a 1983 U-matic Sony video camera, Larrain’s dedication to recreating the look of the period is unswerving. Blending seamlessly with actual news footage and adverts of the time, No‘s aesthetic is entirely rooted in the feel of 1980s television, to its enormous benefit. It may alienate some, but the decrepit video proves more immersive than bothersome. Had No been shot in crisp digital, the contrast between the archive footage and the action following Saavedra might have been too much to take. As it is, there isn’t a barrier between ‘then’ and ‘now’. The consistent visuals promote the organic feeling of enthusiasm similar to that found in No‘s campaign adverts instead of a reserved position, looking back on them from a historical distance.

No locates an unusual time in the modern history of political campaigning. Chile’s ‘No’ campaign saw one of the first instances of politics utilising the language of an entirely different medium, and by foisting pop culture into the realm of political debate, Saavedra and his team arguably crossed an ethical Rubicon long since faded into the distance. No is a rightful celebration of a key moment in Chile’s history when public influence won the day, and a nation embraced their future on a wave of positivity. It doesn’t escape Larrain that that positivity was largely manufactured. By bookending his account of the referendum with scenes of Saavedra showcasing his latest soft drink ads, he chalks up a future of politics-as-product as the price paid for a necessary victory.

Recent Comments