Page One

There are few advance screenings more wracked with nerves then the one for Page One, the latest documentary from Andrew Rossi, the director behind Waiting for Superman and Food, Inc. Sure, Waiting for Superman focused on the utter downfall of the American education system, exposing it as an industry that is literally cheating children out of their own futures. But Page One is about journalists, and it’s being shown to a room full of journalists. And not one of them is exhaling.

The film’s narrative is based around one year at the New York Times, arguably the most prestigious newspaper in print today. We open on the traditional, glorious stereotype of the newsroom. People who seem to have been created by Aaron Sorkin swarm around the New York Times, fighting deadlines, chasing stories and pacing around furiously while on the phone. In short, they are the literal embodiment of THE NEWS, and it’s not hard to become seduced by the whole image. However, before we’re comfortable settling into the All the President’s Men-style narrative, the whole mood of the picture turns ominous. The camera following mainly reporter David Carr, the audience is taken into the woodwork of the failing newspaper industry. We are reminded that The Washington Post, a paper that was instrumental in the coverage of the Watergate scandal, is nearing bankruptcy. We are shown reporters who have worked for The New York Times for over 20 years weeping openly as they leave their desks, explaining that they had received their ‘packet’ asking them to leave their jobs. We are told in no uncertain terms that the internet has slaughtered print journalism.

While the film touches on a vast number of issues, from coverage of the Iraq war to the Wikileaks scandal, the very core of its message remains unwavering: can The New York Times survive the largest journalistic crisis ever to hit mainstream media? And furthermore: can journalism as we know it survive at all?

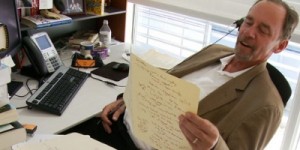

It is here where the documentary’s key character focus, that of David Carr, becomes the most vital. He’s an unlikely hero by any means: an ex-drug addict, it’s difficult for us to decipher his age, but we guess that he is about sixty. His perpetual smoking has turned his speaking voice into a low wheeze, and he seems to spend most of his time slouching around with the demeanour of a homeless person. A younger journalist, already convinced that the paper is dying asks: “David, are you scared?”

Carr barely looks up. “No.” The younger journalist quite patronisingly responds with “David, I’ll ask you again: Are you scared?” Finally, Carr devotes his full attention. “I’m scared of guns. I’m scared of bats. I’m not scared of this.”

Suffice to say, without the characterisation of Carr and a few of his fellow hardened journalists, the film would be a gloomier affair. Carr becomes the touchstone of all that is immovable about the New York Times. When he isn’t writing, he seems to be defending print journalism in debates around the country, and being baffled by things. We are shown the release of the iPad, where we get an eye-roll from Carr. “You know, a lot of people say that Apple saved the music industry. The thing is it didn’t save it on the music industry’s terms.”

Despite the difficulties the New York Times faces, it’s very easy to get swept up in the camaraderie of the newsroom. Just as the Wikileaks scandal is exploding, we see media editor Bruce Headlam getting a call from the Whitehouse, asking him to ‘pass on’ their messages to Wikileaks. “You’re the Whitehouse, can’t you call Wikileaks? Here’s the number: its 1800-Wikileaks.”

What keeps the movie so broadly fascinating is its pacing, as it manages to cover a dozen issues without making any of them feel half-addressed. Perhaps its only downfall is that it casts a too pure light over the New York Times. When a blogger makes a point of the New York Times having an “assumed credibility” that invariably led to the Judith Miller scandal (a journalist who reported the creation of Iraqi WMAs without accurate sources) the point feels somewhat glossed over. Regardless of your political or ideological difficulties, it is doubtless the most gripping documentary of the year, and re-establishes Andrew Rossi as one of cinema’s most involving filmmakers.

Recent Comments