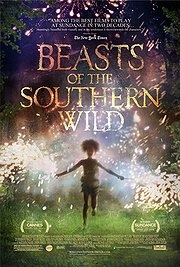

Beasts Of The Southern Wild

Arriving on a wave of enthusiastic critical acclaim, and after having procured the Camera D’or at Cannes this year, Beasts of the Southern Wild has quite a lot to live up to, despite its modest trappings. Shot on 16mm and inhabited by various non-actors, its considerable charm comes largely from some deliberately ramshackle direction that aligns itself squarely with the run-down Delta where the action takes place.

Inhabiting a small island known as ‘The Bathtub’, a small fishing community south of Lousisana exists a world apart from modern civilization. Six year-old Hushpuppy (newcomer Quvenzhané Wallis) is cared for by her rough-hewn father Wink (Dwight Henry), who spends much of the film preparing her for the trials of life, including the eventuality of his death. The Bathtub is hit by a ferocious storm, after which Hushpuppy and Wink must try and salvage some semblance of a future in a world now almost entirely submerged in water.

If it sounds like a bleak proposition, any fears of a sob story are hastily allayed by an unswerving insistence on “no crying allowed”, a mantra repeated by father and daughter that will either come over as jarringly sentimental in its refusal to submit to emotion, or a triumphant stand in the face of hardship. It’s certainly intended as the latter, but Beasts of the Southern Wild‘s general tone is that of a fairy-tale, and the child-like wonder it deploys throughout in the face of a very real natural disaster is both help and hindrance. A child’s-eye view dominates everything, and we are guided through the film by Hushpuppy’s voice-over narration, which has the ability to charm, but ironically removes any possibility of Beasts of the Southern Wild achieving any organic sense of discovery on the part of the audience.

It’s best to roll with the punches in a film brimming with such confidence. When lines like “The whole universe depends on everything fitting together just right” or “When it all goes quiet behind my eyes, I see everything that made me flying around in invisible pieces” appear, the film’s magical realism gets just a bit cloying. It quickly becomes apparent that it might have found a much stronger voice had it done away with Hushpuppy’s narration altogether.

It’s a minor gripe, but in the moments when Hushpuppy’s wonderment goes unchecked by her world-worn father, the film’s otherwise resolute tone of defiance is unbalanced. In fact, the most striking thing about Beasts of the Southern Wild is the relatively conservative message that colours much of Wink’s life lessons. Even if by the end crying is definitely allowed (and indulged in some extremely teary close-ups), the return to “no crying allowed” time and again by Wink echoes the sense of a life hard-won and fought for, defined by self-sufficiency. A distant relative can be found in The Pursuit of Happyness, the message of which went alarmingly beyond a lesson in hard work, with Will Smith actively dreaming of a life swallowed up by the offices of Wall Street. However, with its setting and child’s perspective, Beasts of the Southern Wild doesn’t go overboard with the sentimentality of hard work, being well-grounded in an incredibly assured performance from Quvenzhané Wallis.

Running, screaming and burping her way through the bayou community, Hushpuppy is a wild child in the finest tradition, harking back to the likes of Huckleberry Finn and Eloise. The film’s best sequence comes when she goes with a posse of other displaced children in search of her mother. She talks to her, a blinking light on the water’s horizon, and the film’s efforts of producing a curiously unsentimental sentimentalism nearly crumble. But, approaching it by boat, the light is in fact ‘Elysian Fields’, what appears to be a house of ill repute. Inside, Hushpuppy meets a woman she believes to be her mother. In what might well be a dream, so gorgeous is the lighting and music, the intrepid six year-old only receives another lesson in self-reliance. Held by the woman in a slow waltz, the film’s only moment of genuine heartbreak comes as she is told: “I can’t take care of you.”

It’s hard not to feel manipulated by Beasts of the Southern Wild at times, even if the 16mm and reliably shaky direction do their best to cover it up. But it has so much heart, confidence and brio, that most of Hushpuppy’s moments of wonderment and the overlying magical realism are carried off without the need of thunderous repetition, creating a heady hybrid of fairy-tale and very real survival story.

Recent Comments