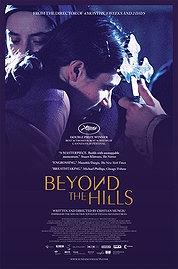

Beyond The Hills

Cosmina Stratan and Cristina Flutur star as Voichita and Alina respectively, two girls who fell in love while growing up together in the same orphanage. Unable to bear living in poverty, Alina moves to Germany where she finds work as a barmaid, but soon returns to Romania to find Voichita and run away with her. The snag is that Voichita has turned to God in the time they have been apart and joined a monastery, which she is reluctant to leave. Put the fact that this film centres on two attractive lesbian nuns aside and you have an achingly tragic love story that questions not so much faith as blind devotion.

From the opening scene you can tell there is a deep connection. Voichita sees Alina from across the platform and tells her to stay put, but Alina hops across the tracks and embraces her companion in floods of tears. Alina clearly longs for Voichita, but Voichita is holding back. In a matter of seconds we are given a wealth of history between these two characters, with very little being said.

The monastery where Voichita lives is so far removed from the rest of society you forget that Beyond The Hills isn’t set in the dark ages. In the monastery, they draw water from a well, light candles in order to see and chop firewood. When Voichita goes into town, she stops at a police station where an officer complains about his laptop. Mother Superior sticks out like a sore thumb at a fully electricity-enabled café, cloaked in black and wearing NHS glasses. The monastery is stuck in a time warp (like their beliefs, one might think) and the contrast between where Voichita lives and where Alina has come from is stark. This works beautifully throughout.

Alina struggles to fit in to Voichita’s new way of life, leading to several clashes with the other Sisters and the sinister ‘Papa’ – the head Priest in charge (and the only man in the monastery) played by Valeriu Andriuta. ‘Papa’ flings out fire and brimstone at every opportunity, demanding that Alina confess her sins – all 464 of them – and instructing the other nuns to brutally, crudely, tie her up in Messianic fashion when she suffers an epileptic fit. For one who claims to be so godly, he is the nastiest person there. At one point he flat out refuses to take Alina in when she comes out of hospital, despite Voichita telling him she has nowhere else to go. His superiority complex is also baffling. ‘Papa’ claims to possess an icon only he can touch that grants wishes, which turns out to be not much more than a framed picture. At one point Alina asks him “Isn’t God for everyone?” and one can’t help but agree. What gives ‘Papa’ the right to keep holy icons from everyone else and throw people of church? Isn’t God everywhere? Again, the question is posed but not answered.

The film artfully treads the balance between religion and science, presenting us with scenarios and leaving the audience to make up their own minds. A deeply religious woman tells Mother Superior that her husband is dying from throat cancer, when Mother Superior instructs her to pray she says that it’s terminal. Is it still worth praying? When Alina is in hospital, Voichita prays over her body and she finally comes to – much to the amazement of her doctors. Did prayer bring her round? Support is never shown in favour of one argument or the other.

Stratan and Flutur jointly won the Cannes Film Festival award for best actress last year, and quite rightly so. They complement each other to a turn: Flutur playing Alina as grim-faced and stoic with an angry streak that only Stratan’s Voichita – pale-eyed, poised and gentle – can abate. The only flaw with this film is Alina’s character arc seems to level off as soon as she arrives at the monastery. She shakes things up, gets tied up/hospitalised, comes back, shakes things up again, is tied up/hospitalised, rinse, repeat. There is little evidence of Alina going on a “journey”. Voichita on the other hand develops wonderfully as the film goes on. Alina’s arrival shakes her faith and motivates her to become someone responsible for their own fate rather than the wide-eyed, obedient wallflower she was when the film began. Scenes between the two actresses are so absorbing and intensely private you find yourself bereft when they are, sadly, parted. You don’t want other characters to interfere, and this is key to establishing a believable relationship.

Beyond The Hills goes much deeper than its premise suggests, throwing light on religion and how it fits into society, if at all. Visually stunning with raw and striking central performances, Beyond The Hills is a movie that is light on action but heavy on moral dilemmas – which is no bad thing.

Recent Comments