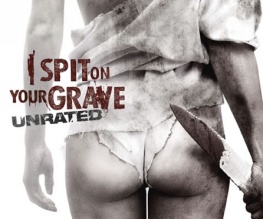

I Spit On Your Grave

The original 1978 version of I Spit On Your Grave – banned in Britain as one of the original ‘video nasties’ until a heavily-censored version cropped up in 2001 – caused outrage and general despair across the US as society started asking itself the Big Questions, such as “Who will save our children?”, “Is it wrong to stare at her bum even though the camera is clearly inviting me to do so?”, and “My tax dollars paid for this?” Maybe not that last, but Roger Ebert’s admission that he felt ‘ashamed’ after viewing it pretty much captured the general reaction and no doubt had director Meir Zarchi and his crew high-fiving themselves into a stupor.

Despite its standing as perhaps the most infamous of the nasties, I Spit On Your Grave Mark 1 is actually relatively little seen by non-horror buffs, which should work in director Steven R. Monroe’s favour when his update hits cinemas. Curious rubberneckers – their interest piqued by the grim tomfoolery of the Saw and Hostel franchises – will see a genuine remake, as opposed to a Rob Zombie-esque “re-imagining”, as writer Jennifer Hills (Sarah Butler) once again unwisely heads for the great outdoors in search of peace, tranquillity and inspiration as she begins work on her new novel.

The locals are all missing teeth or work in a gas station – one even plays the harmonica, so you know she’s in trouble. Four of them in particular take umbrage at her high-falutin’ big city ways and invade her cabin – one, a mentally disabled plumber (a by-the-book Chad Lindberg), is coerced into raping her while the other three record events on a video camera. She briefly manages to escape but fails to take note of horror movie rule number one: When fleeing for your life through a deserted forest, you simply do not trust the first person you bump into. She does, and is subjected to even more torture and repeatedly raped, this time by each member of the gang.

So, Pixar it ain’t. Exploitative it most certainly is. The original had up-in-arms feminists labelling it misogynistic, while a counter-argument claimed it to be a pro-feminist tract, for our heroine does indeed turn the tables and exact an even more gruesome revenge on her tormentors, one by one and with a nice line in dramatic irony. Both readings were, and are, claptrap, I’m afraid – before the term was even invented the original was pure torture porn, and this remake is no different. If anything, it’s a case of the Daddy of them all returning to show the young pretenders (Saw, Hostel et al) exactly how it is done.

And show is most definitely what Monroe does, Hitchcock and Spielberg’s high-brow, big city ideas of true terror lying in the imagination be damned. ISOYG does not want to scare you; it wants to horrify you, and in that respect it’s a success. Even in these jaded times, the film has a few gruesome new parlour tricks up its sleeve – women will shiver, men will cross their legs, clenched buttocks will be universal.

It all looks tremendously draining – not the kind of gig about which actors chirrup platitudes like “Every day was a joy!” – and special mention should go to the fearless Butler, who turns in a raw, feral performance – particularly in the film’s opening hour. Her discomfort will be shared by most of the audience; those who take it in their stride will see it as a solid, ultimately harmless addition to a tiring genre. For better or worse, there will be no repeat of the 1978 histrionics this time around.

Recent Comments