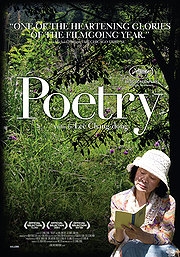

Poetry

Following the story of Mija (veteran Korean actress, Yun Jeong-Hie), Poetry depicts a woman caught in generational limbo. Guardian to her surly teenage grandson, Wook (Lee Da-Wit), she’s twenty years older than most in her position, but – currently in her mid-sixties – she’s not yet as old as the elderly stroke victim she assists as a part-time carer. Rarely able to coax conversation from her neighbours, Mija’s main company is her own and even that is becoming increasingly confusing. With her memory beginning to fail her, she struggles to recall the names of everyday items such as bleach; “we used to call it Clorox”, she tells her doctor, only serving to emphasise her slip from modern social practice. Desperate to communicate – even if only with herself – she turns to a local poetry class in search of her voice. Yet just as Mija seeks to express her thoughts, circumstances ensure she must stay silent.

Told that Wook and his friends were responsible for the repeated rape of female schoolmate, driving the victim to suicide, Mija is encouraged by both the other boys’ fathers to join them in quietly paying off the girl’s mother. With the men convinced that compensation should substitute for punishment, Mija’s hesitance to agree only serves to displace her further, appearing to them as senility rather than morality. With Wook too remaining largely indifferent to his grandmother’s attempts to provoke confession, Mija finds herself firmly on the outskirts of a society she can no longer understand. When she’s eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, the fake flowers present in the doctor’s office seem bitterly apt; in a world defined by keeping up appearances, artificial beauty is all that remains.

In this way, Mija’s disease is almost as fitting as it is cruel. A condition that usually claims its victim’s later memories first, Mija’s dementia forces her to reflect on the past whilst she attempts to make sense of the present. Everybody has a story, an identity that – like natural flowers – will only fade with age. Just as the man she cares for feels that disability has robbed him of his masculinity, the youth Mija spent as an object of men’s desires has been and gone; a relic, it can be looked back on, but never experienced again. We sense the irony, then, when Wook’s friend’s father, desperate to cover up his offspring’s involvement in the loss of a life, anxiously demands to know whether Mija “understands the situation”. Mija is the last person in the group he should ask; she’s the only who does.

With its script well crafted and lead wonderfully acted, it’s almost ironic that the film’s only moments of lag occur during those scenes directly addressing its title – Mija’s poetry classes. However, with Mija’s quest for poetic inspiration providing a framework, it’s the nuances in these scenes that really deliver. Indeed, as our protagonist faces the camera, crying as she recounts her “most beautiful memory”, filmmaker and actress work together to ensure we know exactly why the tears are flowing. Recounting a time when she was just an infant, Mija speaks of the unquantifiable love she shared with a sister presumably now passed on, or out of reach. Recalling the childhood purity we only get one chance to cherish, Mija weeps not just because this is her most beautiful memory, but also because it’s her first – and the one that will be last to leave her.

Recent Comments