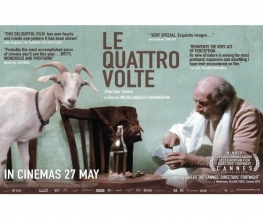

Le Quattro Volte

It’s not every day you get to watch a film where the principal stars are goats. It’s not every day you get to say that said film isn’t a kids animation or a comedy, but a drawn out, entirely wordless Italian art film (about goats). It won’t be for everyone. Le Quattro Volte is as slow as watching the bark grow on a tree at times, but it’s nonetheless a breathtaking snap shot of one small life cycle, with a most grand message.

[FLOWPLAYER=http://uk.image-1.filmtrailer.com/73109.jpg|http://uk.clip-1.filmtrailer.com/4817_22785_a_4.flv,275,180]

Le Quattro Volte roughly translates to ‘the four times’ and refers to the four sections of the film, and of this particular life cycle. With a brief introduction that gives us a clue of what is in store, we are left following the last days of a lonely goatherd, herding his goats with his faithful canine companion. After his death we are left to follow his herd, or more specifically the short lived existence of one baby goat. We are encouraged, it seems, to consider this life cycle as one transient movement; the man’s soul entering the goat’s, perhaps. This is the basic rumination of the entire film. One life ends and feeds another. Every living thing is part of the cycle.

When the goat lies down to die at the foot of a tree, then, we are to follow the tree’s death, as it is cut down and used for a celebration in the town before being turned into charcoal and returned to the town to fuel another life.

The message, then, is big, if not a little trite. What turns it from simply being a series of images of life and death is the deft choices of its director, the fluid narrative throughout and the stunning photography of cinematographer Andrea Locatelli. The shots are at times awe-inspiring images of nature, or, in one instance, the dust in a church floating through a patch of sunlight. We are continually forced to consider the way things grow and live and move in our world. Set in this particular village there is a sense of timelessness that would not be found in even the barely larger, more modern towns.

Whereas a lot of the film is merely life documented, there are some moments when you are forced to question whether they are amazing bits of fortune, or brilliant natural, staged scenes. The main example of this is a wonderful shot in which the camera hovers between two lanes, following a celebratory procession through the village, as the goatherd lies dying in his bed. The man’s dog follows them round the corner, runs ahead and waits for them to pass in a bush. Once they’ve gone he runs back and pulls away the chocks from under the van’s wheels, letting it roll backwards and smash through a fence, releasing the whole goat flock. It’s quite hard to picture how this was achieved in one shot, and quite frankly there should be some kind of animal Oscar available for this dog to win. That, and watching the goats find their way into the bedroom and kitchen of their own herder, are rare moments in the film that make you chuckle.

Clearly, this film is not for the easily bored, or the unimpressed. Without words, or even a score, it could send the most avid art-house aficionados into a beautiful slumber. But stick with it and the way the circle of life is captured may have you looking at the world a little differently. The director manages to grab some wonderful moments of life, whether it be a baby goat bleating, sprawled on the floor exhausted by coming into existence, or the slow zigzag of an ant across an old man’s withered face. They might seem simple, but it’s rare to see such pure, unadulterated life portrayed so candidly on film.

Recent Comments