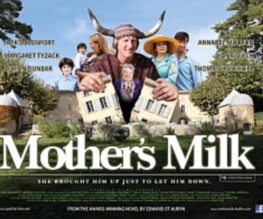

Mother’s Milk

Husband and wife Patrick (Jack Davenport) and Mary (Annabel Mullion) arrive for their usual summer holiday in Provence with their eight year old son Robert (Thomas Underhill) and new born-Thomas. We learn through a flash-back to the mothering bed that the little family are a bit cramped in their house in Scotland, and cannot move to London because ‘the property market has gone mental’. The poor dears. Well, at least they can enjoy themselves kicking it back by the Mediterranean coast for six weeks or so right? Wrong, alas! When will their troubles end? There’s some ghastly Irish charlatan (Adrian Dunbar) at the house running a sort of hippy commune ten months of the year because Patrick’s mother (Margaret Tyzack) has signed over the house to him, and the place is set to fall entirely into his hands upon her death. On top of all that, Mary’s mother Kettle (Diana Quick) is coming to stay, much to the annoyance of everyone it seems.

Despite all the sun and sea and loveliness, no one is happy. Particularly precocious young Robert (we are informed of the inner monologue of many of the characters, including young Bob, through a clunky voice-over device by Tom Hollander, which is actually rather soothing when you tune out), who hates his younger brother for coming along and depriving him of mummy’s attention, and over the course of the film learns to hate almost everyone. His father seems to have the worst of it as far as the film presents it, battling booze, Irishmen, temptation (in the form of former childhood sweetheart Caroline, who also shows up), and most grippingly his maternal ghosts that he needs to be rid of. Davenport is passable in the paternal role, portraying a character we can almost have some sympathy with as he struggles to take responsibility for his life amidst a crew of mostly boozed-up reprobates.

I’ve been told that Edward St Aubyn’s novels, one of which this film adapts, are a combination of Evelyn Waugh and P.G. Wodehouse, “supposedly black humour, but mainly just black” was how a friend put it. I can very well believe that the book this film is based on managed to be a satisfyingly coruscating peep into the ins and outs of middle-class domestic angst, the dark inside their heads contrasting nicely with the white summer sun without them. Mother’s Milk attempts to give us such an essay, but the problem is that the whole situation depicted is entirely without weight. The only heavy aspect of the film is the prospect of the impending death of demented matriarch Eleanor, in a performance by the late Margaret Tyzack that was mooted for a BAFTA nomination but didn’t get one. Certainly some part of me found the idea of her character’s death affecting, but only in the way that the thought of most deaths affect me. I found the fumbling and uncommunicative Eleanor a perfectly vile old witch, heartless and idiotic. Slow handclap for the filmmakers for restraining themselves when it came to the maudlin ‘can-you-forgive-her-she-is-dying-you-know’ sentiments. They succeeded splendidly on that score.

The question I’ve been asking since the film began was ‘why did they bother making this film?’ Then I noticed Melvyn Bragg’s name on the executive producers credit, and straight away the image of Lord Bragg and his baby-boomer generation friends sitting around in a garden in Provence sipping the local wine discussing St Aubyn and how ghastly it is that there is so much trash in the multiplex these days, and yet the dirty public are being deprived of the poignant and humourous delights of St Aubyn! Quickly Dennis, call up the accountant and see if something can be done! All our friends would like it anyway, and let’s have more wine and laugh about how detached we are from reality! Glee! Sickening.

Perhaps I’m being cruel. Mother’s Milk tries hard but it can’t escape the vast chocolate cream cake of self-indulgence that’s hovering above it, the occasional fat crumb falling into the orchard as they try to spout the script with a serious face. 2012 is not the time for this film, and the cinema is certainly not the place for it. Try the BBC in the early nineties next time Melvyn, or the radio. I would have enjoyed an ‘In Our Time’ about middle-class oedipal angst about a thousand times more than this brittle wooden Gallic comfort stick, thanks.

Recent Comments