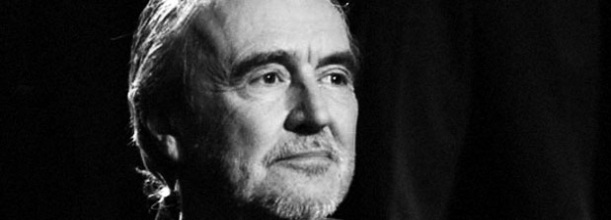

Cheat Sheet: Wes Craven

Name:Wesley Earl “Wes” Craven Date of birth:August 2, 1939 Place of birth:Cleveland, Ohio, USA Special move:Directing and Writing Films include:The Last House on the Left, The Hills have Eyes, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Music of the Heart, My Soul to Take, the Scream franchise |

|

What you probably already know:

Wes Craven’s works have characteristically been associated with the fragility of the dream-state and the potential to manipulate it. The most infamous of such cinematic exploration was inarguably Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), where a malevolent character named Fred Krueger gains access to the real world through the gateway of dreams. The sharply surreal and edgy original went on to spawn five campy, Craven-free sequels, in which Freddy Krueger had essentially been devolved into a figure of fun. But in 1994, Craven reclaimed the concept with Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, casting actors from the films as themselves and having Freddy terrorise them in “real life” – a blurring of the fourth wall of movie-making that hinted at the postmodern spin Craven would utilize two years later in Scream.

Craven has also long been accredited with single-handedly resurrecting and reviving the slasher-flick for the post-80s generations. With his inception of ironic brilliance – Scream (1996), Craven reflected upon the screamfests of old, and a satirical love affair between the audience and the original bad-boys of terror – including Craven’s own Freddy was once more rekindled, and Craven returned to rule over our nightmares with tongue thrust firmly in cheek.

What you might not know:

Craven never went to film school – instead earning a Master’s degree in writing and philosophy – in part because his strict (fundamentalist Baptist) upbringing had taught him to be wary of the corrupting influence of movies. In fact, Craven never actually saw a film until he went to college. Ironically, his directorial debut, The Last House on the Left, would be one of the most controversially graphic works of the 1970s, inciting a widespread, apocalyptic furore. During the first year that the film ran in the US, riots broke out in some theatres, with frenzied activists charging into the projection booths in an attempt to sieze the print and destroy it. In Craven’s very own recollections, theatre owners were threatened, there was a fist-fight in one theatre, a heart-attack in another, and reports of grown men weeping.

Not to be outdone, when Last House on the Left – along with its nefarious reputation – came before the British censors in 1974, it was refused a cinema classification outright. Like its contemporary in celluloid crime – The Texas Chainsaw Massacre – which was similiarly excommunicated from movie houses at around the same time, Craven’s disturbingly vivid portrayal of rape, murder and revenge was considered too much (reality) for the U.K. audience. Only 37 years later, on March 17, 2008, did the BBFC grant the film an 18 certificate with all previous cuts waived.

The graphic exploitative style of The Last House on the Left incited a brutal renaissance in horror film-making, where a new level of gritty, gory realism would subsequently pave the way for the Splat Pack and their recreations of the theme.

Wes Craven quote:

On horror movies: “It’s like boot camp for the psyche. In real life, human beings are packaged in the flimsiest of packages, threatened by real and sometimes horrifying dangers, events like Columbine. But the narrative form puts these fears into a manageable series of events. It gives us a way of thinking rationally about our fears.”

What to say at a dinner party:

“So apparently Wes was called up by agents saying that if he left the Richard Gere-gerbil reference in Scream‘s script, he would never work again…”

What not to say at a dinner party:

“Wasn’t Scream that movie based on Scary Movie?”

Final thought:

As unchallenged overlord of the dark dream-realm and uncomfortable surrealities, Wes Craven is evidently no fan of the mundane real world. But the macabre storyteller’s narratives go beyond mere frights of fancy; Craven’s trademark sharpened wit and edgy commentary pierce the tenebrous boundary between the acceptable and the terrifying, the real versus the imagined, exposing the frightening fluidity of those seemingly disparate ideas. In the chilling dreamscapes of Craven’s construction, there is far more truth than fiction. Welcome to his nightmare…

Recent Comments