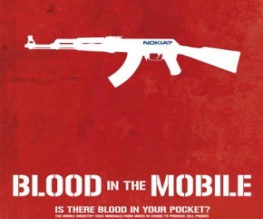

Blood in the Mobile

In the probing documentary Blood in the Mobile, Danish director Frank Poulsen reveals that seemingly all mobile phones (and many other gadgets) contain metals that have been harvested from sites in the middle of warzones; a shocking fact which demonstrates that every mobile phone bought in the developed world indirectly funds warfare in some of the world’s poorest countries.

Poulsen focuses on one country in particular, plunging the audience into the war-stricken Democratic Republic of Congo; a plentiful source of both natural minerals and horrendous violence. However, the documentary doesn’t delve deeply into the cause of civil unrest in Congo, choosing to focus solely on the issue of conflict minerals. To prove how far-reaching the implications of these minerals are, Poulsen travels to cities all over the world, meeting political figures who are trying to put a stop to the trading of these minerals, as well as activist groups who are trying to educate consumers about the origins of their mobiles.

The most hard-hitting feature of the documentary is Poulsen’s trip to a local village during his travels around Congo. In this village, we meet Chance – a sixteen year old boy with a teenage life worth complaining about, having literally slaved away three years of his life in the dark depths of a Bisie mine. A camera follows Chance’s descent into a mine, exposing the appalling conditions that lie beneath the surface. Calling the area a ‘mine’ would be an overstatement; the crack in the earth is stifling, unsafe and crammed with young bodies. The horror is drilled home by Chance’s matter-of-fact comments of how tunnel collapses kill one young miner every month.

We do not observe a somewhat expected emotional outburst from Poulsen, who chooses to let the images alone provoke our empathy. In fact, it is not until he is face-to-door with Nokia – makers of a third of all mobiles worldwide, and an obvious target – that we notice a subjective opinion. Through sheer perseverance, Poulsen manages to meet with a Nokia representative to discuss why they chosen not to publish their supply chain and thereby prevent consumers from finding assurance that their phones have been constructed from safe and legal materials. Along with audience, Poulsen struggles to hide his dismay and outrage when the Nokia spokesperson politely argues that although Nokia are indeed striving for transparency, they must take into account confidentiality issues. This basically translates into a worry that if Nokia are purchasing a new technology, they don’t want other phone manufacturers finding out. Therefore, per Poulsen, they are willing to prioritise profit margins over lives and livelihoods in the developing world.

However, as the documentary progresses, Poulsen learns from other activists that Nokia shouldn’t be portrayed as the big bad wolf, and begins to accept the grim reality that they are simply doing business. Consequently, he reluctantly dismisses the fact that Nokia have barely made any progress in the 10 years since the acknowledgement of the existence of conflict minerals, and instead tries to raise awareness in hopes of future revolutions.

Poulsen’s attitude represents an optimistic yet grounded view of the situation. He is disgusted by the prospect that his mobile phone may contain conflict minerals, but acknowledges the difficulty of surviving without a mobile in the modern world. His own inner conflict highlights how difficult it will be to reach out to consumers; with a technology that is so necessary to a huge portion of the population, will people realistically refrain from using them to stand up for this issue?

The documentary achieves its purpose of raising awareness; what must be done is clear. Without demand, there can be no supply. Therefore, without a public outcry it is unlikely that phone manufacturers will take the ethical option of cutting ties with these illegal sources.

To find out more about the campaign click here, or see Blood in the Mobile in cinemas from 21st October 2011.

Recent Comments