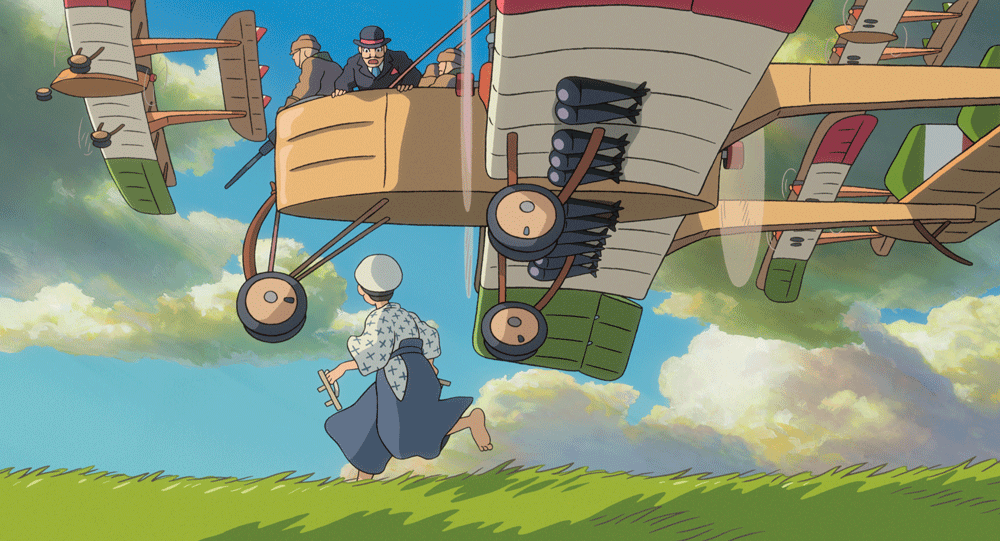

The Wind Rises

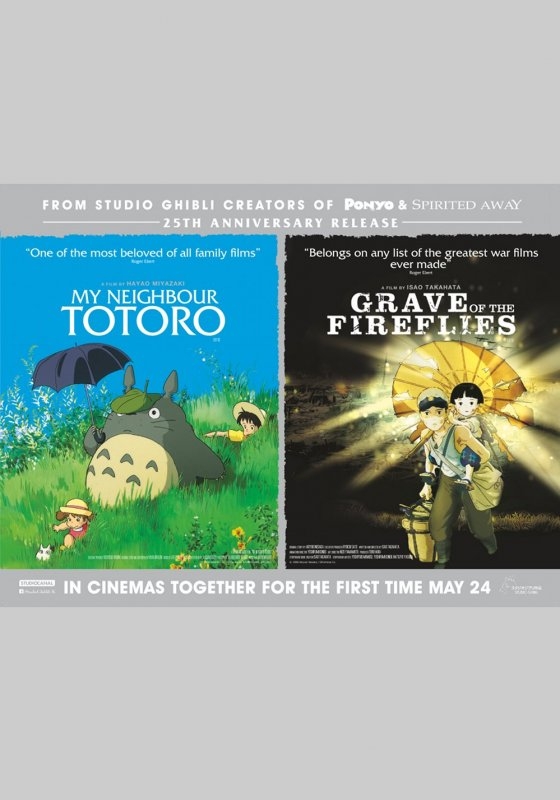

The latest outing from Studio Ghibli and the swan song of possibly the world’s most recognised Japanese director, Hayao Miyazaki, is a wonderful, emotional and quietly reflective film. With tones much closer to Grave of the Fireflies than Ponyo, The Wind Rises will never make it onto most people’s favourite Miyazaki films, but as a piece of art that dissects the creative process, and the career that led up to its inception, it’s memorable, poignant, and bitter-sweet.

The film follows a fictionalised biography of Jiro Horikoshi, the aeronautical engineer who worked for Mitsubishi to design the Zero, the work horse fighter of the Japanese air forces in WWII. In his youth, he has a shared dream with Giovanni Caproni, a celebrated aircraft designer, who instils in him his philosophy – that plane design is a thing of beauty, of art, and that war and profit only ever detract from that vision. Dedicated to his chosen path, Jiro overcomes all that life throws at him to fulfil his dreams.

“The wind rises. We must find a way to live.” – the film begins with these words, and there has been scarce a moment since seeing this film that I have not pondered upon them.

Even without seeing The Wind Rises, it’s evident that this is Miyazaki’s most personal film. Sprinkled throughout his career is a love affair with the connection between flight and art, as seen in My Neighbour Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Spirited Away and, most obviously, Porco Rosso. The Wind Rises feels like the culmination a thousand threads that Miyazaki has been cultivating throughout his career.

The Wind Rises is the most grounded and realistic of all his works, set against real-world events such as the Great Kanto Earthquake and the lead-up to WWII, but Jiro’s extended dream sequences and bursts of creativity keep the film feeling as strangely disconnected from reality as Spirited Away. The difference is that the film never really feels as though it’s going anywhere, mainly because it dispenses with the usual pacing.

There’s no expected end point, no goal, no climax on the horizon, nor does a climax emerge. Jiro feels strangely inert and expressionless in every aspect of his life except for his design his art. While it may make for less of a theatrical event, this structure works as an analogy for the creative process itself, having to pour so much of yourself into your work that everything else feels hollow and unimportant.

The character who ends up receiving the entirety of the audience’s sympathy by the end is Jiro’s eventual lover, Naoko. Jiro is a dreamer, trying to attain lofty and almost meaningless goals in aircraft design for its own sake, and as much as he loves her, as much of a support system for his creative processes as she is, Naoko eventually suffers. And she accepts this, because she loves him.

It’s an incredible, gut-wrenching narrative on sacrifice and the creative process that you wouldn’t expect to see in a Miyazaki film. There have been many interpretations of what exactly he is trying to say about creativity, and in particular how he feels about his own career, but of course Miyazaki is a master storyteller, who only gives enough away to make you waste away precious brain matter pondering what on Earth is he going on about.

Aside from this nuanced introspection, it must be said that The Wind Rises certainly isn’t Miyazaki’s best film. Characters pop in and out as familiar faces, but are never explored further then to provide exposition for global events. Jiro as a protagonist is admirable, but flat. He only develops in 2 distinct ways during the film, the rest of the time he simply feels like a polite, obliging cipher that lacks the moxie and loveability that we’ve come to expect from Miyazaki. Threads are picked up that feels as though they will have enormous impact on the film, and then dropped suddenly.

At the same time, you can’t help but suspect that every one of this “flaws” are really all part of the desired effect.

On a technical scale, the art is as good as its ever been. Seeing 1920s Tokyo being ripped apart by an Earthquake, blueprints in the mind chuffing and huffing their way into life, the nose-dive of a rickety fighter plane, Jiro’s cloudy expression hidden in puffs of cigarette smoke – all this images are wonderful and, for a Studio Ghibli film, as restrained as the storyline. The score is good, even if it doesn’t do much to enhance what’s happening between characters. The Japanese voice acting is, naturally, world class.

In most other animated films, this would be enough to secure a must-see stamp, but the Studio Ghibli grade is much higher.

Have no doubts – this is a fantastic film. You could not have asked for a better farewell from the man who has dominated a genre for the last 30 years. This isn’t an instant classic that transcends language and culture such as My Neighbour Totoro or Princess Mononoke, it’s an exploration of what it took to create those works. Miyazaki has left the field leaving no one in doubt that his was a creative genius that was unparalleled in his time.

With a focus on such beautiful, empty skies, however, Miyazaki is also looking ahead. The skies in The Wind Rises are pregnant with possibility. Yes, it’s as sad a farewell as you could possibly imagine, but for Miyazaki, the wind has risen, and he’s found a way to live.

Recent Comments