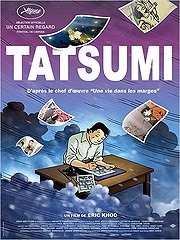

Tatsumi

It’s not often that an artist gets to draw their own biopic, but Yoshihiro Tatsumi has come about as close as is possible. The legendary manga artist’s graphic autobiography was the inspiration for Singaporean director Eric Khoo’s unique accolade to Tatsumi, the man credited with originating the dark and countercultural ‘gekiga’ style of manga in the 1950s. Blending an animated account of Tatsumi’s own life with challenging and often graphic adaptations of some of his most famous gekiga short stories, Tatsumi is truly beautiful. Just make sure you do your reading before you go to see it.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, ambitious young artist Yoshihiro Tatsumi wants nothing more than to draw manga for a living. Initially thwarted by his disapproving father, he resolves to leave home and make his living with his art – and not long after, his first book is published to universal acclaim. But just as some Western comic book writers were forced to adopt the term ‘graphic novel’ to differentiate their serious, adult work from the thin nonsense consumed by children, so Tatsumi and his fellow manga artists struggle with the perceptions of their difficult and often graphic work. Tatsumi coins the term ‘gekiga’ (‘dramatic pictures’) and the rest, as the Japanese almost certainly don’t say, is rekishi.

Interspersed with Tatsumi’s life story are a series of five of his stories, all perfect examples of just why gekiga needed to be differentiated from common-or-garden manga – largely animated in a distinctive monochrome style typical of the art form, they are unashamedly dark and utterly gripping. In one, a businessman on his way to retirement resolves to blow his pension on a grand affair before his grasping wife and son-in-law can get their hands on it; in another, a photographer exploring the remains of Hiroshima makes his name and his fortune when he finds an incredible image burnt into a ruined house. Or does he? As the audience is whisked from amputation to incest via a monkey, a prostitute and a public toilet with some very interesting graffiti, Tatsumi’s story gradually becomes clear.

Viewed as an artistic achievement, Tatsumi is utterly joyous. From the deceptively simple opening sequence, scored (as is the entire film) by director Eric Khoo’s teenage son, the film’s visuals pick a delicate path between naturalism and the stylised anime action with which we are all familiar. The delineation between Tatsumi’s story (in bold colour) and the flickery, sepia-toned vignettes imparts a wonderful sense of swooping between different realities. Once you’ve crossed over, though, you may not like what you find – the voice cast is excellently eerie at times, and Tatsumi’s inspired but unsettling gekiga plough through taboos and horrors like so much mist.

Elsewhere, however, there are cracks in the dreamscape. The subtitles are mesmerisingly clunky and detract from the action at crucial points when the audience really doesn’t need to be frantically rephrasing them, and the biopic elements of the film travel at such a speed that a basic grounding in Tatsumi’s life and the history of gekiga (ideally obtained from the book on which the film is based, one supposes) is absolutely necessary in order to keep up. The frequently shocking gekiga extracts also tend towards what feels like gratuitous violence and very contrived sex, although here Khoo is very much at the mercy of Tatsumi’s originals.

Whilst it might not be an ideal introduction to the eponymous artist or his work, Tatsumi is a beautifully wrought and thoughtfully constructed film with a lot to recommend it. Do a little homework, then track it down – you’ll enjoy it all the more for understanding what you’re looking at, and when a great big glob of semen’s sliding down the screen it’s nice to have a little artistic context…

Recent Comments