On The Adventures of Prince Achmed and the silhouette film

“I could cut silhouettes almost as soon as I could manage to hold a pair of scissors,” wrote Lotte Reiniger in a 1936 article for Sight and Sound. When she was but a little girl, there wasn’t a distinction in Lotte’s mind between her ability to read and the talent that came to define her life. She would cut silhouettes for every birthday in the family and stage Shakespeare plays in a tiny shadow theatre of her own making. In 1923, the young Berlin banker Louis Hagen offered 24-year-old Reiniger the opportunity of a lifetime: to produce the first feature-length animation film in cinema’s relatively brief history. It would take three years of arduous work before the project was complete.

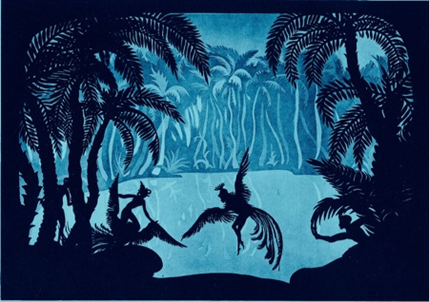

The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) is a marvel on every level—a film of such beauty and scope, yet so delicate and expressive. The plot is a pastiche of Arabian Nights. Its pleasures I will leave for you to discover. Suffice to say that it features an evil sorcerer, a virtuous witch, a fat Chinese emperor, a hunchbacked dwarf, a harem of competitive beauties, a pair of maidens in feathered garments, jugglers, conjurers, dancers, demons, a flying horse, a giant viper and Aladdin’s lamp with all its magical powers. It’s dramatic and funny, often concurrently so, and it breathes the spirit of invention. You can practically feel the excitement of its makers as they discerned the animation tricks we now take for granted.

There is so much in Prince Achmed for the modern viewer to discover. The dreamlike, translucent backgrounds, the intricate tapestry of veils and patterned curtains, of tree branches and thinning leaves, the meticulous rendering of hands shaped to emote, fine details like the rippled reflections in the water, the wizardry of transfiguration sequences. Reiniger cut her marionettes out of black cardboard and thin lead, limb by limb, and joined them up with wire hinges. The silhouettes were lit up from below and filmed from above, frame by frame. The young German filmmaker studied natural movement and, as Philip Kemp observed, “was years ahead of her time in the subtlety and narrative fluidity of her animation”.

Steven Spielberg once labelled the parting of the waves in The Ten Commandments (1956) as the greatest special effect in the history of cinema; an accomplishment he would never be able to top. Of course, he added, you have to frame technological achievement within the context of its time. A great deal of Prince Achmed falls within the same category of technical breakthrough, though it may take a leap of imagination on our part to appreciate it.

The movement of Aladdin’s boat on the waves, so common by today’s animation standards, was a carefully orchestrated innovation that made contributor Walter Ruttmann “very proud”. The starry sky, designed by Berthold Bartosch, comprised three layers of transparent paper on different glass plates, which moved at accelerating speeds to achieve the effect: It remains a wondrous sight, even to the modern eye.

For all the timelessness of its storytelling and technique, some elements of Prince Achmed have undoubtedly dated, sociologically speaking. To Kemp, the comical treatment of the Chinese appears “racially suspect”. Female critic Tim Brayton laments the film’s “retrograde gender politics” in her review — the only piece Rotten Tomatoes (the megaplex of online film criticism) has on its database so far.

In fact, considering its status as the ultimate pioneer, surprisingly little has been written about Reiniger’s first feature film. Its delayed US premiere (in 1942) and post-WWII anti-German sentiments may have contributed to the director being, in the words of animation critic William Moritz, “rather undervalued”. Walt Disney’s relentless marketing campaign to assign Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) the label of “first feature-length animation film” certainly didn’t help.

For whatever reason, and despite the considerable skill that goes into its creation, the silhouette never transcended its condition as a minor art. The term’s etymology may be to blame. Rather than bearing a traditional Latin/ancient-Greek root, it’s named after the Marquis Etienne de Silhouette, who was the Parisian Controller-General of Finance in 1779. As Reiniger recounts in her book Shadow Theatres and Shadow Films, “at this time the finances of France were in a deplorable condition and the Marquis had to enforce severe economies in order to save the country. However good his intentions were, he received little thanks. Everything mean and cheap was called a ‘silhouette’ in a derisive sense, to mock his stringency”. The emerging popularity of black scissor-cut portraits, which were so much cheaper to produce than painted miniatures, sealed Silhouette’s unexpected immortality.

And yet, beyond all else, the elegant craftsmanship of Reiniger’s cut-outs remains the film’s greatest triumph. “She was born with magic hands,” remarked Jean Renoir—the French auteur who championed Prince Achmed before it became a worldwide sensation. Katja Raganelli, who produced a documentary about the German animator, said that cutting silhouettes was her subject’s “lifelong addiction”. Alfred Happ, a friend of Reiniger, tells this story: We would eulogise Lotte and call her an artist, and she would simply say, “I’m not an artist; I’m an entertainer.” I doubt she saw the latter as a lesser feat.

By Alex Gruzenberg

“The Adventures of Prince Achmed” will play with a live musical score by The Prinz Achmed Orchestra at the Pipeline (94 Middlesex Street, E1 7DA) on 19 November at 8pm. Tickets can be purchased at autumnshift.co.uk, or on the door.

Alex Gruzenberg is a friend of Autumn Shift and a freelance writer. His film blog has been shortlisted for the Guardian Student Media Awards, in the Critic of the Year category.

Recent Comments