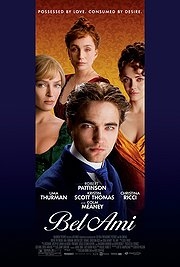

Bel Ami

Guy de Maupassant’s wickedly satirical 1885 novel Bel Ami is transformed into a series of unaffecting love stories by directors Nick Ormerod and Declan Donnellan, finally taking to the screen after decades of theatre work. Everyone’s favourite glittery vampire Robert Pattinson does his best with a dull role and a very modest helping of talent, but his conquests are the real stars of the show in what critics everywhere are calling “the new Cruel Intentions“, because critics everywhere are quite dizzyingly boring.

A few months after leaving the army, the attractive but unaccomplished Georges Duroy (Pattinson) has come to Paris and found a job as a railway clerk. However, a chance meeting with his old comrade Charles Forestier (Glenister), now the well-connected political editor of a popular newspaper, promises an escape from his distressingly ordinary existence. Duroy cadges a dinner invitation and is promptly taken with Forestier’s witty and self-assured wife Madeleine (Thurman), who persuades her husband to give Duroy a column in which to recount his military adventures. Unfortunately, Duroy is barely literate and relies on Madeleine to dictate ‘his’ articles, an arrangement which he seeks to cement by drawing her into an affair. Mme Forestier elegantly spurns him, but observes that “You should call on Clotilde… her husband’s so often away.”

‘Clotilde’ is Mme de Marelle (Ricci), a wealthy and bored young wife who is more than happy to install Duroy in a) a gilded apartment and b) whatever French ladies keep under their petticoats. Charming despite his lack of urbane polish, Duroy is an immediate hit with Clotilde’s infant daughter (who affectionately rechristens him ‘Bel Ami’), and from then on appears to decide that she’s the only female in Paris that he isn’t going to roger. Applying himself to the business of adultery with the single-minded verve of a shark whose wife is in Bristol for the weekend, Duroy methodically begins to elevate his status by means of bedding and ruthlessly manipulating the most influential women he can find; it’s as if Patrick Bateman swapped New York, Dorsia and chainsaws for Paris, the Moulin Rouge and his penis. Will Duroy’s ambition or his lust ever be satisfied, or will his reckless swordsmanship doom him? Anything could happen, and if it involves ‘some more sex’ or ‘a woman crying’ then it probably will.

When published, Bel Ami was intended as a ruthless attack on the journalistic establishment of Belle Époque Paris. Nobody seems to have mentioned this to Declan Donnelly and Nick Ormerod, whose cinema debut demotes Deroy from antiheroic cad to blank-eyed cocksman and swaps the biting social commentary of its inspiration for smouldering glances and gratuitous shots of Christina Ricci’s tits. But even if they missed the point, the co-directors partially redeem themselves with their absolute adherence to the adage of Maupassant’s contemporary Oscar Wilde: “In matters of grave importance, style, not sincerity, is the vital thing”. You may feel nothing for Duroy, Clotilde and the rest, but you will at least be feeling it in a perfectly realised world which, whether the action is in Forestier’s elegant town house or Duroy’s grimy garret, evokes its chosen time with a confidence few costume dramas can emulate.

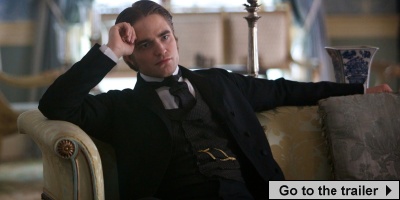

Robert Pattinson is perfectly acceptable as the pale, intense, black-clad Duroy (although I’m not convinced his is a performance which will help him leave behind the pale, intense, black-clad Edward Cullen), but there is no real depth to be found in either the writing or execution of his role. Perhaps dear R-Pattz will surprise us yet, but he’ll need to do more than smoulder if he is to shake off the peculiar curse of being the star of a successful but critically derided franchise. It hardly matters, however, because Duroy is little more than the catalyst which allows us a glimpse of his conquests when they’re feeling less than refined. All three leading ladies are hugely enjoyable. Ricci transforms from a flirt to a heartbroken ex-coquette with panache, bosom heaving as she prostrates herself on a variety of couches (shagging/sobbing, for the use of), whilst Uma Thurman has most of the best lines and all of the best looks as the insightful and fiery Madeleine, a woman determined not to be swayed by Bel Ami’s charms. Oddly, Kristin Scott Thomas is probably the weakest of the trio, with her trembling Virginie (the wife of Duroy’s chief editor) a thoroughly inadequate role for such a powerful actress. Other men pop up here and there, but they contribute little more than moustaches and disapproval.

I rather think that in other hands this could have been an excellent film. There are certainly no bad performances amongst the lead cast, and from an aesthetic point of view everything from the cinematography to the soundtrack was masterfully assembled, but something about it simply doesn’t convince. Are we expected to be such amoral monsters that Duroy’s callous actions don’t even move us? A charmingly outrageous antihero is one thing, but Duroy is portrayed with so little care that he ceases to become a morally intriguing figure and ends up simply a spark sent to ignite rows, tears and yet more erotically charged glances flickering from half-closed eyes. The moral of the story is… actually, who knows?

This review was originally published on the marvellous Mookychick website.

Recent Comments