A tribute to Minority Report

*Spoiler Alert – this tribute to Minority Report contains plot details of Minority Report. If you’re one of those berks who thinks that knowing what’s going to happen in a film will stop you enjoying it, then just go watch Minority Report, have a hand-shandy (you’ll want one, it’s a very good movie), and come back in an hour and a half*

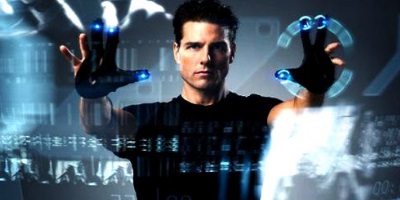

Hey guys, riddle me this: what is Steven Spielberg’s greatest film? You’re dead, dead wrong. It isn’t any of the ones you’re thinking of. It’s not E.T, it’s not Schindler’s List, it’s not Indiana Jones and it most certainly isn’t bloody War Horse (THAT HORSE DOESN’T KNOW YOU EXIST KID, STOP THINKING IT’S YOUR MATE!). No, Steven Spielberg’s greatest film is sci-fi thriller Minority Report… by a bloody mile.

Fact: there isn’t a single day goes by when I don’t want to watch Minority Report. I can’t think of a single life-event, no matter how wonderful or momentous it was, that wouldn’t have been improved by the addition of that film. My first kiss, my graduation, my first paycheque, losing my virginity – all of these and more would have been better if Tom Cruise was going all face-melty in a dystopian future somewhere in the room.

I don’t normally dig sci-fi. That is to say, most of what I love is overwhelmingly grounded in realism. Most sci-fi begins with a big chunk of exposition basically saying “this is what you need to understand in order to get the entire rest of the film – it’s a bit dumb but there’s a ‘splosion later and some pow-pow lasers that you’ll ruddy love,” and whatever. I just don’t go for pow-pow lasers y’know? Minority Report also has this opening section, but it’s so succinct and brilliant that it immediately throws you into the film. Two wooden balls roll down what’s essentially a badass marble run (who else loved marble runs? Minority Report’s got your back) and reveals the name of a victim(s) and a murderer. The opening section then cuts between a mad scramble at the head of pre-crime to pinpoint the location of the murder about to be committed, as well as the real time events at said location – a husband about to go to work, a wife trying to discourage him from playing hooky so she can have her lover over (on this note, if you’re having an affair and suspect your husband might be a bit of a mental, why not go shag at his place? Just a thought).

At this point the audience doesn’t really know what’s going to happen. We’re being introduced to the entire concept of the film, something completely new to us. We see how the location is scouted out, how the agents arrive at the scene, how the pre-cognitives predict what’s going to happen. Instead of dialogue heavy exposition telling us what we need to know, Spielberg opens the film with an intense, action sequence – he chucks his audience in at the deep end and knows we won’t flounder. What’s brilliant too is that not only does Spielberg show how pre-crime works successfully, he also shows how morally ambiguous and problematic it is, again planting a narrative seed that will bloom later on down the line. Following this rollercoaster opening comes an advertisement for pre-crime that plugs any gaps that may still be there – pre-crime is a government initiative, murder wiped out, future-telling freaks yadda yadda yadda. You got it. Film begins.

Except the film doesn’t pan out in the way the opening scenes have you think it might. Cruise, initially introduced as the saviour, is then immediately shown up to be an emotionally scarred, chemically dependent, self-serving protagonist, both crippled and motivated by the death of his young son years before. He believes only in the infallibility of the system within which he works…that is until the system comes after him, at which point he begins to probe deep into the belly of pre-crime to figure out whether or not he could have an alternate future. Throw in the presence of a slimy, slithering villain (Colin Farrell’s great, isn’t he? We’d be pals I bet) and you have the perfect recipe for sizzling on-screen conflict.

Spielberg never lets us get comfortable with whether or not Cruise is indeed a would-be killer, allowing him to go through all manner of physical changes and death-defying stunts to escape his pursuers. Despite his claims of innocence, that he has no idea who the man is he will kill, he is still led to the scene of the crime and carries out the murder just as predicted, though importantly, a couple of seconds too late – these seconds are crucial to proving the fallibility of pre-crime, they show the act not to be evidence of manifest destiny, but instead a conscious decision motivated by Cruise and Cruise alone – one that he didn’t have to carry through, and one that lands him in the horrific prison in the bowels of pre-crime, part of the flock.

And the best thing? The story isn’t even over yet! Cruise has killed the man we knew he was going to kill, he’s been imprisoned, but the mystery of the drowned woman in the lake – the key to everything – isn’t revealed until the very end, and, when it is revealed, it’s done with all the tension of a Kubrickian horror, a crowd of delighted dignitaries struck dumb when confronted with the founder of pre-crime murdering an innocent woman in order to keep a hold of her gifted daughter, in one of the finest twists in cinema.

Minority Report is a film that combines tremendous performances with exceptionally directed action sequences, white-knuckling moments of tension and a whole raft of philosophical meditations on destiny, responsibility, guilt and such like. A faultless example of Hollywood at its pinnacle.

Recent Comments