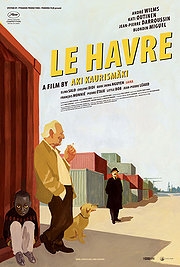

Le Havre

Prolific filmmaker Abi Kaurismaki doesn’t have many limits or particular themes that he obsessively revolves around. Best known for films as diverse as Leningrad Cowboys Go America, about a Soviet rock band touring America, and comical crime caper I Hired a Contract Killer, he likes to keep viewers guessing about his next move. Le Havre certainly brings down the tempo from some of the director’s more eccentric efforts, leading us to anticipate dramatic climaxes and plot twists that never materialise as Karismaki encourages us to embrace this film’s good, honest simplicity.

In the quiet, unassuming French port city of Le Havre, ageing shoe-shiner Marcel Marx (Wilms) has his lunchbreak unexpectedly disrupted by discovering a young African boy waist-high in the water of the docks. Looking surprisingly well-kept considering he’s just smuggled himself into the country, and without ever revealing exactly where he came from, Idrissa (Miguel) may as well have been sent down from heaven – a supposition that, given his effects on the community in which he finds himself, may not be that unreasonable. The kind-hearted Marcel decides to help the boy, hiding him in his house while trying to find a way to ship him off to London where his mother awaits him.

Idrissa’s predicament – how to make it to London whilst avoiding the French border controls – brings out the best in all those around him, as everyone in the community does their part to help. A slew of deadpan, apparently detached performances provide an amusing counterpoint to the genuine kind-heartedness shown by just about all the characters. Jean-Pierre Darroussin as the police investigator Monet is particularly captivating; donning a dark trenchcoat and hat, his constant spying on Marcel conceals the fact that he’s actually trying to help him and Idrissa. As with many of the characters – from the neighbour who provides Marcel with food, to the dock worker who offers to transport Idrissa at no charge – there is no rational explanation or motive for why Monet feels the urge to give his aid, but it’s the unforced nature of his kindness that really makes it feel so warming.

Kaurismaki employs a quirky mixture of realism and melodrama in Le Havre that gives the film a slightly fairy-tale feel. The conditions of Marcel’s life are difficult, reinforced by the fact that his wife Arletty (Outinen) is terminally ill. However, the film’s occasional flashes of the kind of loving lines and swelling music you’d expect to find in a classic Hollywood film lend a feeling that the narrative is more reliant on sentiment than grittiness. The world portrayed here is one of karma, where good deeds yield good happenings, infusing the film with a strange kind of understated wholesomeness about the human urge to help others.

<

For all its positive vibes and optimism about human nature, Le Havre lacks the edginess to make you feel like a happy ending is ever in doubt. Granted, this was presumably Karismaki’s intention, but the paucity of moments where it seems like the forces of the world are working against the characters makes the film’s central mission – delivering Idrissa safely to London – feel almost too easy. That’s probably just my brainwashed mind though, which has been so grinded down by mainstream, overly plot-twisted trash that it has trouble processing a film depicting people being truly selfless. While there is little actual ‘drama’ here, Kaurismaki’s unique blend of realism and slightly magical melodrama engages us with its deadpan charm, showing that, in the right circumstances, the human race isn’t all that bad after all.

Recent Comments