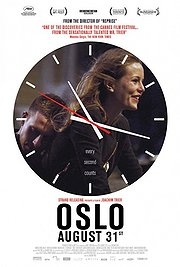

Oslo, August 31st

DON’T DO DRUGS. Like, ever. Bad things happen. Whereas Trainspotting taught us the horrifying short term effects of drug abuse (ceiling babies and meandering toilet dips do not appeal), Oslo, August 31st focuses on the long-term effects on both the user and those who care about the addict.

Trier sets the scene in an unusual fashion; presenting locations within Oslo, with anecdotal voiceovers of memories born in the city. We are then introduced to our protagonist, Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie), who proceeds to fill his pockets with rocks whilst walking into a river, a la Virginia Woolf. After a suspenseful moment, he resurfaces. We then watch him plod his way back to an impressive stately home-esque building – a drug rehabilitation centre.

The film primarily centres on a 24-hour period that Anders is given to attend an interview in his hometown of Oslo. Anders takes full advantage of the ‘free pass’, visiting family members and old friends, calling lost loves – actions that we come to recognise as a desperate search for meaning in his directionless life.

Trier has essentially created a focused character study, with little attention paid to the plot. This decision worked most of the time, but as the film progresses it does tend to feel somewhat tedious. We are only shown situations that involve Anders, with the exception of a few landscape shots to document the setting. Therefore a strong lead role is neccessary, and thankfully Danielsen doesn’t disappoint. The direction style is very personable, with many close-up shots of Anders, giving the audience a meticulous view of his reactions, enabling access to a greater understanding of his psychological state. A particularly effective scene presents Anders listening to conversations in the middle of a crowded café. The jumbled voices peter out as he isolates a single voice (which is all the audience hear too) before imagining what their private lives are like – they are always envisioned in a depressed manner as soon as they’re alone. This scene effectively demonstrates how isolated Anders feels, as well as his outlook that no one has a chance of happiness.

Ultimately, it takes a lot of effort and hard work to restart one’s life at the age of 34 – and to Anders’ demotivated mind, it all seems too much. What could have been a predictable tale of a depressed man learning that life is worth living, actually grows into a bleakly realistic story of a life misspent. The characters Anders meet lead realistic, problem-filled lives, rather than representing idealistically glowing examples of what a drug-free life could provide. The film acknowledges that everyone has it hard, and in doing this, emphasises how self-pitying and hopeless Anders has become. It is difficult to find sympathy as we watch his half-hearted attempt at a drug-free life spiral back to his old ways, leaving Anders with his finger firmly pressed on the self-destruct button.

Due to Anders’ melancholic attitude, it’s difficult to feel much for him. You begin to empathise more with those who care for him, as you can understand their frustration in the face of his hopelessness. Through these interactions we gain an interesting perspective on the side of drug addiction that is usually ignored; the challenging integration back into society, and the sacrifices others must make in order to save the addict they love. Anders’ parents sell their home to fund his expensive stint in rehab, his sister’s trust in him is broken and his ex-girlfriend has cut him out of her life completely after enduring heart-breaking hunts for him during his drugged-up days.

Unfortunately, the frustration wasn’t enough to invoke a powerful emotion towards Anders; therefore the potentially moving finale left me with overwhelming indifference. Perhaps this was the bleak intention, but I believe that Trier wanted an attachment to form between Anders and the audience, so that we would be hoping against hope that Anders would make the right decision.

Recent Comments