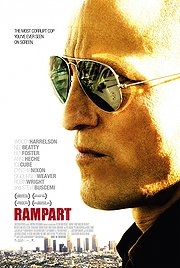

Rampart

Every decade needs to have a couple of defining ‘corrupt cop’ films. In the 90s we were treated to the original Bad Lieutenant and the sprawling LA Confidential, while the noughties gave us hits like Training Day and The Departed. The iconic examples can be divided into two general categories. The former two are morally ambiguous, and blur the lines between good guys and bad guys; the latter are definite battles against corruption, with the baddies getting their own in the end. Yet Rampart doesn’t easily fit either category, and is a surprisingly intimate study into a man who has lost touch with both his family and his job, despite his desperation to keep both.

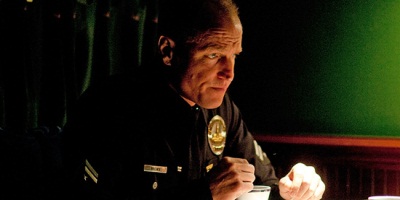

Rampart follows veteran police officer David Brown (Woody Harrelson), who is constantly battling scandals over his renegade behaviour on the job. Nicknamed ‘Date Rape’ by his colleagues due to an ongoing case in which he allegedly killed a suspected rapist, and involved in various acts of police brutality and dodgy dealings, Brown struggles to adapt to what’s expected of him. On top of this, he is trying to maintain some respect in his own family, which, like the police force, is beginning to see him as a dead weight and liability.

Plucky though Brown is in talking his way out of trouble, his reckless actions are those of a Neanderthal; a man unfit for a society which has seemingly changed too fast for him to keep up. He is a sex addict, and his urges lead him to sleep with criminal lawyer Linda Fentress (Robin Wright) who it turns out is investigating a major case against him. He is prone to bouts of rage, and has no qualms about killing should there be a chance for personal gain. As his abuse of police powers becomes increasingly clumsy, he isolates himself from those who once supported him, and becomes a lone wolf desperately fighting for survival.

Despite Brown’s mean streak, Harrelson’s screen presence is too damn likeable for us to hate him. His wild eyes reveal a growing paranoia and confusion about why the whole world seems to be falling apart around him, and it’s clear that he’s motivated by a misdirected desire to keep his family together. Harrelson’s performance shifts effortlessly between the wild and the weary, giving Brown an emotional depth that makes his descent sad – albeit inevitable – to watch. The narrative is driven by the charismatic character of Brown, who is presented as a stick-in-the-mud rather than someone who’s necessarily corrupt. Despite his repugnant and philandering character, Brown is charming, smooth-talking and genuinely determined to keep his unstable family together. His ability to keep his superiors in the force (small appearances from Sigourney Weaver and Steve Buscemi) at bay using big words and legal jargon is always amusing to watch, as Harrelson infuses the character with a relish in dismissing fusty old authority.

The screenplay, co-written by director Oren Moverman and James Ellroy (the author of LA Confidential), is sharp and cynical. There is hardly a moment where the growing pressure on Brown lets up, and along the way we are treated to some brilliant lines; Brown’s declaration that ‘I don’t cheat on my taxes… you can’t cheat on something you never committed to’ has genuine potential to become a popular catch-phrase in this age of austerity. One aspect that feels under-written is Brown’s growing paranoia. Depicted by Brown peeking manically through Venetian blinds and ranting at people that they’re ‘against him,’ there isn’t enough going on around him, or enough cinematic trickery, for us to really share his sense of persecution.

The film sleekly combines stylishness and introspection. Moverman demonstrates a playful deftness with the camera, approaching typical scenes like three-way conversations or someone watching TV in new and effective ways. This is contrasted by more intimate, classically-shot scenes in which the camera lingers on Brown as he grows increasingly strained by a world in which he seems to have no place. As expected from a seedy cop film, Rampart is mostly nocturnal, and this is complemented by warm, soft lighting to give the whole thing a neo-noir feel.

Rampart is already a front-runner to be one of the decade’s definitive corrupt cop films. Focusing more heavily on the financial strains and crisis of masculinity that they may cause, it’s a film that could, over the next few years, speak to a growing number of people who’ll inevitably be feeling similar pressures to Brown. Moverman’s entertaining style and Harrelson’s ability to be all of charming, repulsive and touching strikes a great balance. It may not be as ambitious or as clever as some of the great cop dramas of previous decades, but it certainly gives an interesting, more intimate slant on the genre.

Recent Comments