The Way of the Morris

The quintessential Englishness of Morris dancing may explain why, before Monday, I had never heard of it. “You know, Morris dancing” clarified my articulate English peers, who then proceeded to raise their legs and clap a bit. “Oh, right” says I, still baffled.

Way of the Morris, a documentary film by Tim Plester and Rob Curry, answers my curiosity with more eloquence. Morris dancing is apparently a traditional folk dance that has been practiced by troupes of men in rural villages all over England for centuries. Somewhat of a national joke, Morris dancing involves bells, flowery hats and sometimes sticks. Admittedly, it’s not an incredibly impressive thing to watch, and at times it looks like a very bucolic Pride parade. However, Plester’s documentary succeeds in that it recounts not only the history of the dance, but also his personal ancestry and lineage within the tradition.

The film is as much a bildungsroman for Plester as it is a documentary. The film sees Plester returning to his hometown of Adderbury, North Oxfordshire in an attempt to understand the tradition of Morris dancing. Plester explains that while his father, uncle and grandfather were devoted Morris men, he has never danced. Whether you understand that as being a big deal or not, the film portrays an oddly moving take on Plester’s heritage. Super 8 footage of his childhood is cut alongside modern day Addebury, skilfully portraying the village as a sort of pastoral paradise. You sort of spend the whole movie thinking: “Sod this city life. I’m going to move to Oxfordshire and drink locally brewed stout and eat scones with clotted cream. And when I get old I will still appear robust and glow with health. And I will marry a Morris Man.”

Perhaps most involving about the documentary is the Adderbury Village Morris Men themselves. They are generally middle aged or older, respected pillars of the society, and by Christ do they love to dance. “Young people, I suspect, think “Ooh, look at them old farts. Dressed up like Morris dancers.” Says Bryan Sheppard, one of the prominent Morris men of the community “Then they go off to Uni, move back and think “That’s a bit interesting. Tell me more about it.” And they realise how important Morris dancing is to this village.”

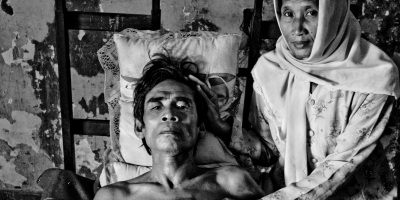

The exact origins of Morris dancing are lost to history, but Plester attempts to cobble together a history from loose local knowledge. Originating around the Iberian Peninsula, “Morris” is said to be a corruption of the word “Moorish”, an antiquated word for those of North African or Muslim descent. Plester has little interest in the exact origins of Morris dancing however, his main focus being on what it means rather than what it is. He investigates World War 1 as it affected the Adderbury Morris Men, when only a single Morris returned from the battlefield. The war, as Plester eloquently phrases “disrupted history’s continuum” and hence wiped out Morris dancing in the village for decades afterwards. The tradition was re-invigorated in the 1970’s, with much help from the emerging folk-rock genre that was popular.

Here, Plester grants us an audience with folk-rock legends Billy Bragg and Chris Leslie of the Fairport Convention. Their enthusiasm for Morris is obviously strong, but their inclusion feels like standard documentary filmmaking tokenism, known as the Third-Act Celebrity Appearance. They add little to flush out a rapidly thinning story. While Morris is an interesting cultural titbit, it struggles to command a full film. The film’s narration quickly becomes over-eager and searches perhaps too hard for an emotional climax – Plester finally choosing to dance at a Morris festival – when there is little to go on. He dances, he goes home. While the movie is well-made and beautifully shot, Plester’s closing thoughts on Morris dancing echo the mood of the movie “When it works, it works only in context.”

Recent Comments