Island

Island marks the filmmaking debut of Brek Taylor & Elizabeth Mitchell. Adapted from the eponymous novel by Jane Rogers, it tells the story of Nikki Black (Natalie Press) a 29-year-old Londoner with an unhappy history of abuse, neglect and a penchant for fairy stories. A foster child from a very young age, Nikki journeys to a remote Hebridean island in order to confront, and kill, the mother who abandoned her at birth.

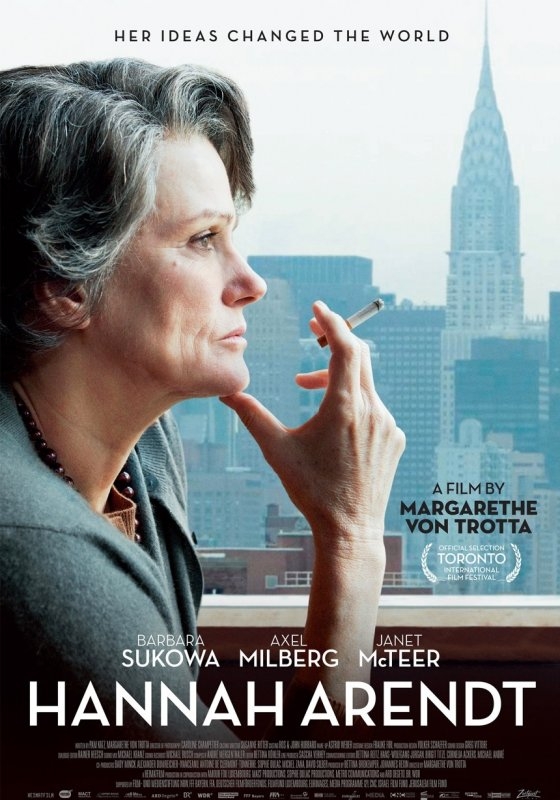

Soon after arriving on the island Nikki discovers that Phyllis (Janet McTeer), her birth mother, has a spare room advertised in the local post office. This results in Nikki moving in with her would-be victim, Phyllis, and her unwitting half-brother, Calum (Colin Morgan).

What unfolds is a tense drama as Nikki, prone to flashbacks and sudden attacks of anxiety, struggles to come to terms with her erstwhile abandonment and her very current desire for revenge. The moments of tension between Nikki and Phyllis are given something of a relief in the scenes which explore Nikki and Calum’s developing friendship, one based on their mutual love of story-telling. However this second narrative thread, with its deeply troubling sexual undercurrent never truly provides complete respite from the tension of the first, and in fact ultimately becomes the central source of anxiety for the audience.

The two main threads combine to form a thrilling narrative which, upon its conclusion, demonstrates a wonderful symmetry – one that is not unlike that of a typical fairy tale or Greek myth. This ‘fairy tale’ theme is one that also bleeds into the aesthetic of the film, most obviously in the surrounding landscape – numerous shots of gnarled and twisted old trees, arched over winding footpaths recall any number of Grimm’s Fairy tales. And perhaps more subtly it’s also evident in the shambling and dark set Phyllis, in her tiny cottage, surrounded by her various medicines which somewhat resemble potions.

These subtle details are not the escapist imaginings of Nikki, they are definitely ‘real’ but they are also not fantastic enough to be evidence that the ‘real’ world is definitely one of magic. Island, therefore, engenders a much more subtle approach to the blending of fantasy and reality, the outcome of which is a true ambiguity about the nature of events. This is an ambiguity that other films such as, for example, Guillermo Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, although brilliant in their own right, don’t quite realise.

The wonderful subtleties of the plot are supported by three brilliant and nuanced central performances. Press particularly makes a fantastic lead – her shrill townie intonations sounding almost unbearably coarse when set against the serene clam of the rural island landscape. And coarser still when in dialogue with her half-brother, the softly-spoken Calum whose awkward innocence and naivety is portrayed superbly by Colin Morgan. Michael Price should also be commended for his droning, ambient soundscape which haunts the film throughout and lends a further sense of mystery to events.

Island is a tense and ultimately tragic fairy tale of neglect, revenge and finally redemption. It is magic realism done with a remarkable lightness of touch that is, unlike similar films, effortlessly and satisfyingly ambiguous.

Recent Comments