The Love Punch and the plague of the terrible film

Along with Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot, Agatha Christie created a slew of lesser known but also great detectives. These include Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, a pair of charming and resourceful marrieds that feature in four novels. The first time we meet them they’re in their twenties, the war has just ended, and they need something to do. The last time they show up (in the last book good old Aggie wrote) they’re in the seventies, as intrepid as ever.

I bring it up because I wish so much that when Joel Hopkins decided to make a film about retiring baby boomers doing an adventure, he’d just adapted Postern of Fate instead of writing something from scratch. I would be so much less angry if he’d just adapted some Christie. I wouldn’t have ranted to four separate people over the last hour, and people would still think I was a normal human.

When I was sent to review The Love Punch I thought I knew what I was in for. I thought I’d get a mildly unenjoyable film that at the end of the day was just not made for me. What I got was something that inspired such rage it was a miracle I didn’t punch the projecter.

Let me set for you the scene:

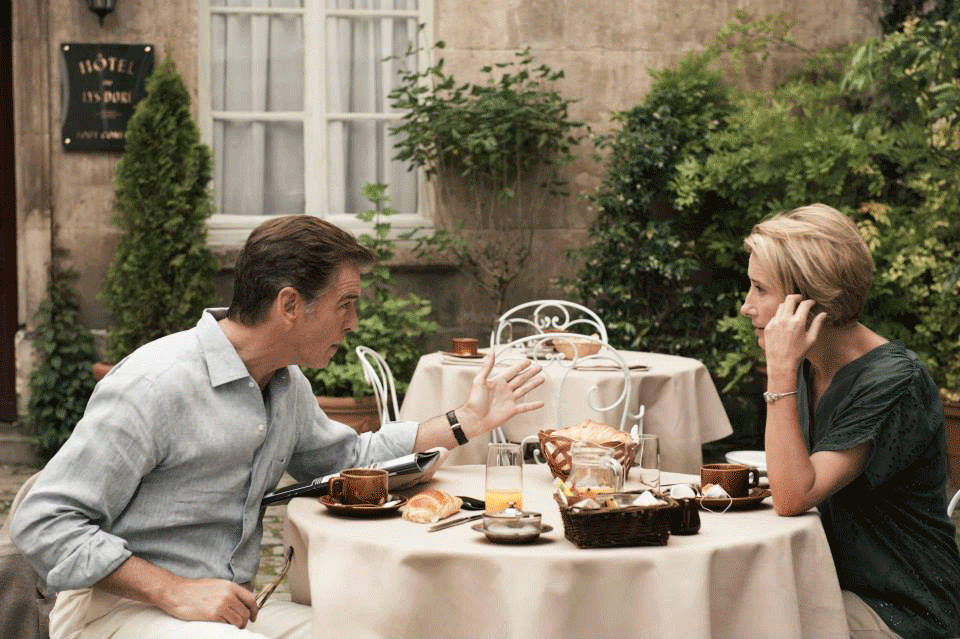

The film opens at a wedding. Don’t ask whose wedding; it doesn’t matter whose wedding. You will literally never see their faces or hear about them again. At the bar there are two glamorous older people. They are Emma Thompson and Pierce Brosnan. Within a minute, and with all the subtlety of a drunk rhinoceros recounting his latest booze up in Ibitha, you are told that they used to be married, and that they’re friends with Celia Imrie and Timothy Spall. Which you can’t fault them for, who wouldn’t be friends with Celia Imrie and Timothy Spall?

There is actually an entire scene in which nothing happens, and we learn only that Pierce Brosnan and Emma Thompson are divorced, a fact we might have been able to glean later by her repeated references to their failed marriage.

Next thing we know it’s Monday morning and Pierce and Emma are both watching people leave. Pierce is bidding farewell to his much younger lover, who’s left him, and Emma to her daughter, who’s going away to university. You will never see these characters again.

Pierce heads off to start his final week at work. He’s the head of some company or other, and he’s retiring just as the company’s been sold. But when he gets there he finds that the new owner has immediately sent the company into receivership, and everyone there has lost their jobs, their retirement funds, and any chance of a severance package, and the shares they have are worthless. (Why do they have shares if the whole company was sold? No one knows the answer.) Pierce is broke now. Emma is broke now. Their kids are broke now.

Everyone is going to be so comparatively poor.

Pierce and Emma are unable to find any information about the internationally trading company that bought them out on said company’s public website. They need a password. Fortunately, they can Skype their son (a character who literally exists purely to provide IT solutions and to have an amusing housemate who keeps going for a dump or a wank with doors open even though he knows perfectly well there’s someone else in the house.) and he can get them a password in thirty seconds. Win!

They head to Paris to confront the dastardly Dan (Laurent Lafitte), who admits to his wrongdoing but points out that it’s entirely legal, and gives a hearty laugh in their faces while you, in the audience, start to question the writer’s understanding of mergers and acquisitions.

Realising they have no legal recourse by which to regain their lost wealth, Emma and Pierce decide to do a heist. They recruit Celia and Timothy and head to the south of France to infiltrate Dan’s wedding and steal a ludicrous diamond. (His name is not Dan, but dammit is he dastardly)

Now, I am not the target audience for this film, and I can accept that. I can accept that while the best films transcend genre and demographic, there are plenty that are designed to appeal only to a select audience, and that do their job adequately, at the very least. But what I cannot accept is the presupposition that because your target audience is specific and relatively small, they do not deserve a well-told story. Worse, this particular example assumes that the demographic is downright stupid.

Because the audience is older, they won’t question a jeweler being able to create an exact replica of a necklace he’s never seen, in less than a day Because they’re older they won’t mind the fact that when our two protagonists GET SHOT AT IN PUBLIC, their response is to simply park the car and toddle off.

Because the audience is older, they’ll take anything, so there’s little point in turning out a well-researched, well-developed, cohesive film.

There is no excuse for this kind of laziness.

There’s a huge amount of talk at the moment about the need for more and better roles for women, and The Love Punch proves that we need to be fighting for more than that. There are so many incredible actors being aged out of the industry, forced to side-step into thinly drawn characters in lackluster films, lackluster, I sometimes suspect, simply because the filmmakers don’t think it’s really worth the time. So we need more and better roles for older actors.

(We also need more and better roles for ethnic minorities, for actors who aren’t the size of my left thigh, et cetera, et cetera…)

The thing that makes The Love Punch so unbelievably frustrating (apart from the obvious pandering and condescension) is that there really is a market for a film along these lines. Like Breaking Bad and The Pink Panther had a torrid and ultimately doomed affair, and their resultant child was raised by the conservative middle class and lived a perfectly normal life until it reached its twilight years and grew into its birthright.

A cleverly written script about a diamond heist pulled together by inexperienced baby boomers with a core cast as good as this one could be genuinely great. Because the cast is great.

Emma Thompson is a goddess, we know this. Celia Imrie and Timothy Spall are delightful, and Pierce Brosnan is very suave. It’s agonising to watch actors of this caliber being so goddamn professional with this kind of material, even without remembering that Thompsons is and ACADEMY AWARD WINNING SCREENWRITER.

And it’s not an isolated problem.

Zack Snyder repeatedly makes films based on the assumption that twenty-something men will be happy with only boobs and explosions.

Katherine Heigl has a career (yes, still, she still has a career) because so many producers believe women will be happy as long as someone gets married.

Tropes and clichés are thrown in in place of real character development and a compelling plot, and commanding huge budgets. It makes a mockery of all the independent filmmakers struggling to cobble together the funds for enough gaffer tape to hold their battered lights together, and it flagrantly spits in the face of everyone who sacrificed their time and money to see the film.

The Love Punch probably got green lit off the back of one or more of its stars, presumably Emma Thompson who worked with writer/director Joel Hopkins on Last Chance Harvey. It’s easy to understand why the film got made; it’s less easy to understand why none of the many people who must have read the script bothered to speak up about its complete lack of believable character motivation.

I can only imagine that they oversimplified the needs of their intended audiences. They thought beloved actors playing ordinary people doing bizarre things would be enough. It isn’t, and it never will be.

What audiences crave, what they deserve, is genuine connection. Characters they believe in, in a story that makes sense, however wildly things go off the rails for our characters.

The Love Punch is a terrible film. So terrible that I actually wanted its characters to die at one point (would have given it an extra star if they had) and there’s no excuse.

The audience, however small, deserved better.

Recent Comments