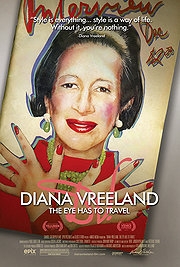

Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has To Travel

For its target audience, that youthful, hungry crowd raised on Ray-Bans, Doc Martens and Diet Coke, The Eye Has To Travel can hardly be beaten. Drawn altogether more sympathetically than Anna Wintour in The September Issue, Diana Vreeland’s larger-than-life persona is lovingly rendered in that ‘perfect’ red she so strived for, in broad and fine strokes alike by her granddaughter-in-law, director Lisa Immordino Vreeland.

The film follows the life and work of Diana Vreeland, who had celebrated tenures at both Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, discovering Lauren Bacall and our very own Marks & Spencer superstar Twiggy along the way. Professional and personal reminiscences of Mrs. Vreeland are threaded throughout the film, from fashion rockstars David Bailey and Yves Saint Laurent to Addams Family matriarch Anjelica Huston; all of this is spoken over by that unmistakable gravel-in-a-bubble-wrap-lined-blender voice, and it’s just so easy to slip under her spell.

Her upbringing in Paris, her marriage to Reed Vreeland and her relationship with her children are acknowledged, but not dwelled upon; curiously, at no point does the film descend into E! True Hollywood Story tales of sexy intrigue. It’s easy to tell that further digging into her relationship with the mother who called Mrs. Vreeland her “ugly little monster” would make for the sort of Jeremy Kyle melodrama everyone secretly adores – there are times when you want to hear less about Mrs. Vreeland’s larger-than-large Costume Institute exhibitions and more about why her sons seem so disappointed by her. Paul Cantelon (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and The Other Boleyn Girl) composed the music, which with its vibrancy and percussion frustratingly hints at the obviously-crackers way a person who solemnly believed that the bikini was “the most important thing since the atom bomb” had to have conducted their private life.

For non-fashion enthusiasts, The Eye Has To Travel is peculiar in that it still has much to offer. In the course of the film, one of the 40 or so talking heads makes note of the fact that unlike so many of our fashion greats of today, Diana Vreeland did not boast a stellar fashion education background; her work was instinctive in a way that you lose the instant you walk into a place where people purport to shape that instinct. What becomes clear in her comparatively late rise to greatness (she became the editor of Vogue in her fifties) is that before Mrs. Vreeland became instrumental in the civilisation rising up around her, she immersed herself in it. She lived it before she shaped it; a stark contrast to our educational ideals of prolonging childhood in conjunction with pumping into young people a knowledge of a world they’ve never experienced. She forces you to think about how you know what you think you know – who would you be if no one told you how to be? It takes maturity and a wealth of life experience to look these questions in the eye; that Mrs. Vreeland (and indeed, the Mrs. Vreeland who directed) can do it with such style and grace is to be applauded.

Though it’s not how Mrs. Vreeland would have wanted you to think about life, The Eye Has To Travel shows you an example of solipsism that is unique, special and could only have come from the fashion world. The malleability of the world around her is something Mrs. Vreeland realised early on – when asked if a story she was telling was fact or fiction, she simply replied, “Faction!”. We’re shown that the only thing Mrs. Vreeland considered unchangeable and true was herself; a champion of the bikini, blue jeans, leopard prints and a whole host of so-called superficial fripperies which changed the landscape of how we present ourselves to one another, she stuck to her rouged cheeks, jet-black coiffure and adoration of red throughout. See it as pathological vanity, see it as unadulterated intellectual freedom, whatever you like – it would, however, be wrong to see it as superficial idiocy.

Recent Comments