Alps

When Dogtooth was released in 2010, it certainly took us by surprise. Contemporary Greek cinema doesn’t get much of a look-in on the world stage, and the air of discovery that trailed in its brutal wake helped Dogtooth become a popular word-of-mouth sleeper. By the time it had been nominated for an Academy Award, it had single-handedly established Yorgos Lanthimos as a name to watch. Michael Haneke’s influence has been duly trotted out, his gruesome 1997 home invasion flick Funny Games an obvious bedfellow of Dogtooth. Both share a perverted glee in forcing audiences to confront shocking, unexplained acts of living room terrorism. However, Lanthimos’s vision of a family broken by violence is a shade stranger, the assault of Dogtooth emerging from within the walls of its unassuming compound. While Lanthimos keeps a veil between the unnamed father’s systematic degradation of his children and the motives behind it, it serves to enhance the film’s overall weirdness and confirm it as both unknowable and completely beguiling.

It seems unfair to describe the originality of Dogtooth and Lanthimos’s distinctive style as familiar territory, but Alps can’t help feeling like a companion piece within the first few minutes of its drily funny opening scene. Empty save a lone gymnast and her trainer, a gym is filled with the overblown opening strains of Carmina Burana. After completing her routine, the young girl asks her trainer why he doesn’t let her perform to pop music. “I know when someone is ready for pop” he deadpans, adding that if she bothers him again with such requests he’ll break every bone in her body. Then she won’t be able to do rhythmic gymnastics to pop, or any other kind of music. It’s an amusing exchange delivered in a calm and slow monotone, the humour sadistic and dry as a bone.

The two form half of a group christened the Alps, who provide a service for the bereaved. Taking the place of recently departed friends or family, they spend time playing out rehearsed scenes with people in mourning, in the hopes that it will ease the process. Taking their names from the titular mountain range, lonely nurse Monte Rosa keeps quiet her decision to stand in for a young tennis player killed in a car accident. Beginning to enjoy the family life offered by the girl’s devastated parents in the face of her own uncommunicative father, Rosa finds herself in danger of becoming too attached and incurring the wrath of malevolent head Alp Mont Blanc for her deception.

It’s a doozy of an idea, and this being Lanthimos, the execution is expectedly slow and steady. Sadly, the funereal pace extends to an acute lethargy at the heart of Alps, which can’t shake off a feeling of underachievement as its refusal to dig a little deeper negates any mystery and starts to frustrate as events totter onward. It just feels like too rich a concept to be given the silent treatment, which is essentially what Lanthimos does via the deliberately stilted, poker-faced performances. It wouldn’t be so bad if those hiring the Alps weren’t so ossified themselves. Everyone communicates with everyone else in the same studied timbre, and the distinction between who’s acting for whom becomes blurred.

This might have been a clear part of Lanthimos’s M.O. in deciding on such an understated tone, but any message conveyed therein is lost in silence. The droll humour that peppers Alps (“I don’t go to funerals”) stops things from becoming interminable, and there are even a few surprisingly sweet moments. The Alps themselves are not immune to the tragedy of loss, with the aforementioned gym trainer Matterhorn completely bewildered by the idea of getting a haircut when his barber dies. In an act of selfless quid-pro-quo, Rosa obliges to help him if he lets his student try out a pop song for her gymnastic routine. It’s a wry segment that also manages to wrongfoot expectations of awkward sexual coercion, Lanthimos apparently well aware of the niche he’s carved for himself.

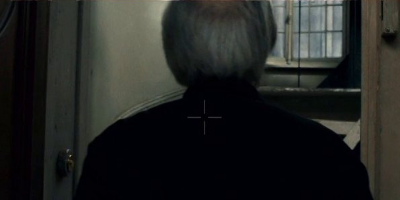

The Alps may be a group, but any sense of unity is quickly dashed by clear distinctions of rank and worth. Lanthimos’s isolating camera pushes perspective into sub-aquatic realms of shallow-focus intimacy, much of Alps following the back of Rosa’s head, filling the frame and rendering everything outside it a blurry haze. It’s a startling impression of her loneliness and alienation, and only deepens the sadness of her relative animation within the Alps and outside the shuffling miasma of their employers. Dogtooth‘s own sinister calm in the face of outlandish absurdity triumphed as Lanthimos gifted audiences a character outside of the madness in the family’s suffering cleaner, Christina. Her presence conferred a zoo-like status on the disturbing family compound, which helped keep Dogtooth a bizarre enigma held at arm’s length. In Alps, it seems everyone in Athens is playing along with the same inert gag, and we’re embedded right in the thick of it. It makes for just as weird a film, though not half as wonderful.

Recent Comments