Michael H. Profession: Director

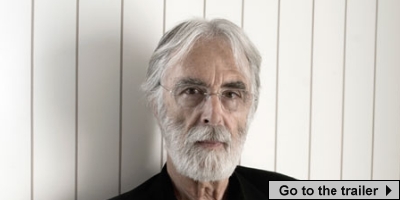

Michael Haneke, with his iconic eyebrows, is an intriguing fellow. His films have been met with controversy because of their relentless austerity, harsh depiction of violence and because they can cause a strange reaction in the viewer: of anger, or even guilt. This has resulted in both criticism and praise. Some find it easy to resent his seemingly hypocritical lecture on violence, given his infatuation with depicting it himself. But, as Michael H. Profession: Director explores, this unpleasant viewing experience is precisely why Haneke films are so fascinating. In his opening speech Haneke claims he only “attempts to approach the truth” and “take the viewer seriously”. He implicates the viewer into his films, continually drawing attention to their construction and the viewing process so that we are forced to consider them not as cinema, but as real life. As this documentary explores, Haneke doesn’t want to merely entertain, he wants to challenge, polarise, and deeply, deeply disturb.

Michael H. Profession: Director takes each of Haneke’s films individually, from Amour (2012) to The Seventh Continent (1989), and discusses them with impressive care and insight. The film begins with a seemingly intimate fly-on-the-wall shot of Haneke brushing his teeth at home. But the scene, with its unflashy set and greyish lighting, is distinctly Hanekesque. We follow him into a spooky corridor where there is a sound of running water and the floor is flooded, he nervously shouts “is anyone there?” and then the whole scene suddenly rewinds in front of our eyes and cuts to Haneke watching the footage of himself brushing his teeth…

Montmayeur chose an interesting way to start the film. He reflects Haneke’s technique (used famously in Caché and Benny’s Video) of encouraging the viewer to presume something is real but then suddenly and unexpectedly revealing that nothing is as it seems. Haneke isn’t at home! He’s plotting the dream sequence in Amour, where Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) ventures into the flooded hallway and a disembodied hand appears from nowhere to gag him. We get to see Haneke’s active and meticulous directing style: he’s a self confessed “control freak” and clearly has every moment visualised before shooting. This technique of Montmayeur’s of combining audition footage, location scouting, rehearsal and then a clip from the final film is satisfyingly in-depth and is later repeated with key moments in Haneke’s other films.

As is clear from the fake Haneke Twitter page, in which the joke is that he tweets things he wouldn’t usually say (“I make movies and I love my cat even though he stinks. Lol #catfart”) he is renowned for his chilly, and often pretentious, demeanor. This is certainly reaffirmed in the film. On the Amour shoot he throws a hissy fit screaming: “SILENCE! My GOD! No Talking! you’re making me SICK!” In an interview Jean-Lois Trintignant admits “Everyone knows he’s a guy you’d better not screw with. We don’t have fun, he has fun. We’re all afraid. It’s very tense”. That saying, we do get a glimpse at his nice side too, there’s even one bit when he lovingly encourages one of the child actors from The White Ribbon to do an enthusiastic air guitar version of Deep Purple’s Smoke on the Water. Montmayeur also jokes with Haneke that it’s impossible to get a still shot of him because he playfully moves around a lot “like a child”.

There are so many interesting and intimate moments in this film. Haneke explains that the scene in The White Ribbon when the young boy asks his sister about death is “heavily marked by personal experience” and was based on a conversation he had when he was a young. He also provides insight into the infamous dream sequence in Cache when a child violently slaughters a chicken: “I deal with all my fears and insecurities through my work. That’s why I don’t need a psychiatrist”. There are scenes when he’s enthusiastically lecturing at a university in Vienna and tells the camera funny stories, like when he was asked to direct a Hollywood action film. Footage of Haneke and his films are also inter-cut with interviews from collaborators including Isabelle Huppert, Juliette Binoche and Emanuelle Riva – who all agree that old Michael H. is a genius, but working on his films isn’t the most fun thing to do.

Seeing clips of Haneke’s films side by side really reveals his unique style and the fact he has created a specific and recognisable universe that spans his work. Unfortunately the interviews are limited to friends and collaborators so there are times when it seems slightly biased in its affection for the director rather than a thorough critical study. However, overall Michael H. Profession: Director is well made, entertaining and informative.

Recent Comments