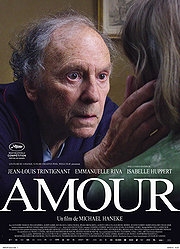

Amour

Amour tells the story of an elderly couple, Georges and Anne. After Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) is paralysed down the right side of her body by a stroke, Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is left to tend to her. Georges is forced to cope with the enormous amount of physical care she now requires, along with Anne’s increasing malaise and suicidal tendencies, with little support from his adult daughter Eva (Isabelle Huppert).

Amour is the latest work by famed director Michael Haneke, known his bleak and haunting approach to the problems of modern life. His previous films include The Piano Teacher (bleak, haunting, uncompromising) and The White Ribbon (bleak, haunting, uncompromising) which also won the Palme d’Or for best film at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival. Amour is most definitely a Haneke film. It has his creative style, the quick edits, the subtle motifs in cinematography and script, even the bloody interior design screams Haneke. Amour, however, is set apart even from his previous body of work.

Amour is dominated by a constant sense of impending doom. The opening scene sets this atmosphere up, with the fire department breaking into Georges and Anne’s home and discovering their bedroom delicately decorated with flowers and Anne, in her finest clothes, dead. Knowing the inevitable end, the rest of the film is devoid of any hope of a happy outcome, but it is almost beside the point: the film is attempting to explore emotion rather than a series of events. In fact, Georges tells us so. In a breakfast after Anne’s first stroke, Georges describes a story from his youth, where he came home from the cinema utterly miserable, having seen a film that left him in tears. He can barely remember what the film was about, or what happened when an older boy saw him crying but, as Georges says, it is not about the details of a film, the only important part are the emotions you take away.

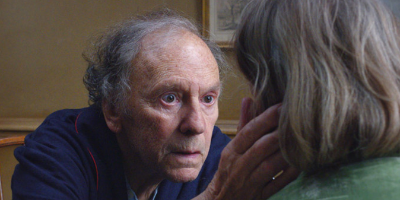

It is the same with Amour. After the morning with the initial stroke, the film continues telling the story with quick cuts. Extended scenes will lead on to relatively short glimpses of George trying to cope – lifting Anne off the toilet, say, or helping her with her exercises. Any sense of time is lost. This film could be set over weeks or months. This, along with the fact that almost the entire film is spent inside their apartment, creates a terrible claustrophobia. He loves his wife, and deals with Anne’s needs well, but the film creates a prison around him. Eventually, this develops into two types of prisons. In one he his bound to the needs and demands of Anne, in which he must sacrifice everything for her, because of his deep and unerring love. The other is created by Anne’s humiliation at being so infantilised, and her resultant wish to end it all. Georges’ own helplessness is not physical like Anne’s, it is through the contradictory states of wanting Anne to live, yet seeing her in such pain.

George is an extremely stoic character. To represent that side of Georges we are never privy to, Haneke employs the most masterful use of visual motifs. The film uses windows for remarkable effect from the very first scene. The piano is also used subtly yet powerfully. The first time we even realise there is a ruddy great piano in their living room is when Anne’s former piano student (Alexandre Tharaud playing himself) pays them a visit. It is only at that moment we understand how much the stoke has really cost Anne.

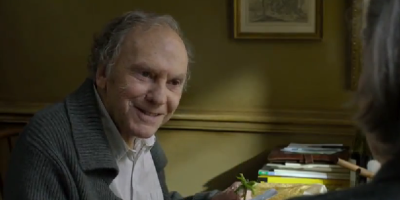

Every scene, every moment, every gesture is perfect. While other great films may also be minutely controlled for perfection (take any Stanley Kubrick film, for instance) the difference in Amour is that not a single moment feels as though it is part of a script. Georges and Anne cease to be actors, or characters. It is almost too natural, too realistic. A person who has even remotely felt any of the emotions on display in this film will find it hard to watch, and even harder to look away. Without needing to manipulate the viewer with a string-heavy score or a sappy speech, the film captures you in the most vulnerable recess of your mind. The two central performances by Trintignant and Riva deserve every accolade they get. Riva manages to convey an ocean’s worth of emotion using just her eyes.

What is truly special about Amour is that nothing is forced on you: every tear you might shed feels completely genuine and gut-wrenching. For myself, I begun to weep openly around the 45 minute mark and, as cynical and jaded as I am, I did not stop until the end of the film. A scene involving a pigeon was especially victorious at lubricating my eyes. Amour is beautifully, thoughtfully, wonderfully depressing. It is entirely unpretentious, makes no attempt to manipulate your emotions, and does not try to moralise on the topic of euthanasia. It is remarkable in that it drips with care and forethought, yet there is no real narrative here. As Georges states, it is not the details of a film that is important, it is only the emotion. Amour has that like no other film. Be warned: you’re going to carry the weight of Amour with you for years.

Recent Comments