Michael

It has been long established in cinema that sometimes the most ordinary personas can mask the most unexpected secrets. From Ed Wood’s semi-autobiographical take on a troubled cross-dresser in Glen or Glenda, to Anthony Perkins’ meek portrayal of a deranged killer in Psycho, films have helped us to realise that it’s hard to know what people get up to behind closed doors, let alone understand why. Yet perhaps too often the most dangerous of these characters are depicted as withdrawn from society – reclusive hermits with a difficult past and a fondness for taxidermy. Many of us keep secrets, so why should we believe that those with the darker ones are lurking in the shadows, rather than hidden in plain sight? If there’s one message Michael makes clear, it’s that the boundaries between the everyday and the horrifying may not always be as wide as we think.

Opening with its protagonist’s return home after a presumably average day, the film wastes no time in creating a matter-of-fact atmosphere. As middle-aged Michael (Fuith) parks up at his house in the Austrian suburbs and begins to unload his shopping, the scene borders on the mundane. Seeing him carry a bulk buy of toilet paper to the basement, it’s easier to assume he’s bargain hunter than a beast. But as he begins to fry up three steaks and lays two places at his dinner table, it seems unusual that there’s no sign of a guest; that is until Michael opens up the dark, basement cupboard and a young boy (Rauchenberger) shuffles reluctantly into view.

Though any doubts as to the disturbing nature of the relationship are quickly dealt with (we witness the aftermath of Michael’s urges as he cleans himself in the bathroom sink), by allowing the interactions between his two leads to vary in tone, Schleinzer raises a number of intriguing – if uncomfortable – questions about Michael’s mindset. Sometimes he appears as an awkward father figure, happy to let his captive stay up until 9pm watching TV, or to spend the day completing a jigsaw puzzle together, but quick to be angered by any sign of either boredom or youthful exuberance. On other occasions he himself seems to play the childish role, in one instance eagerly attempting to start an indoor snowball fight with his understandably unamused prisoner.

Though any doubts as to the disturbing nature of the relationship are quickly dealt with (we witness the aftermath of Michael’s urges as he cleans himself in the bathroom sink), by allowing the interactions between his two leads to vary in tone, Schleinzer raises a number of intriguing – if uncomfortable – questions about Michael’s mindset. Sometimes he appears as an awkward father figure, happy to let his captive stay up until 9pm watching TV, or to spend the day completing a jigsaw puzzle together, but quick to be angered by any sign of either boredom or youthful exuberance. On other occasions he himself seems to play the childish role, in one instance eagerly attempting to start an indoor snowball fight with his understandably unamused prisoner.

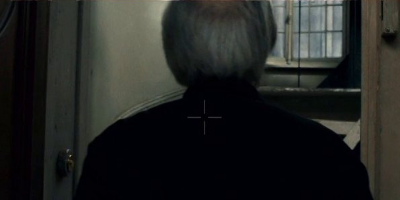

Offsetting this are Michael’s communications with other adults, which – conversely – prove unsettling through their familiarity. Though he is by no means shown to be popular, there is equally nothing conspicuous enough about Michael’s day-to-day life to mark it out as unusual. He chats to colleagues, attends a skiing holiday with friends, and even engages in flirtation with a barmaid. It is left unanswered as to whether this later action is indicative of a complex sexuality, or of a determination to feel normal.

Offsetting this are Michael’s communications with other adults, which – conversely – prove unsettling through their familiarity. Though he is by no means shown to be popular, there is equally nothing conspicuous enough about Michael’s day-to-day life to mark it out as unusual. He chats to colleagues, attends a skiing holiday with friends, and even engages in flirtation with a barmaid. It is left unanswered as to whether this later action is indicative of a complex sexuality, or of a determination to feel normal.

Though it remains vital that we never pity Michael, it is through humanising him that the film truly captures the abject horror of his deeds. Coupling this with the use of largely stationary camera shots, Schleinzer displays his subject in a manner entirely free of stylisation, providing a story that doesn’t simply say “look at this monster”, but instead says “monsters exist.” As the film reaches its conclusion, it becomes clear that the latter approach is not only more grounded, but also far more troubling.

Recent Comments