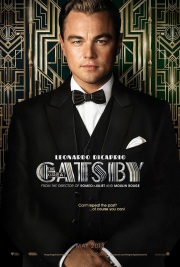

The Great Gatsby

There are few that would deny F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel, The Great Gatsby, is a modern classic. Set in New York, 1922, its plot centres on young and mysterious Long Island millionaire, Jay Gatsby (DiCaprio in the film), and his longing for beautiful socialite Daisy Buchanan (here played by Mulligan). Gatsby may own the largest house, host the biggest parties and drive the fastest car, but only having Daisy would make him truly happy. Meanwhile, the man that has her, Daisy’s boorish husband Tom (Edgerton), only wants more, pursuing an extramarital affair with a mechanic’s wife named Myrtle (Fisher). With Gatsby’s neighbour and Daisy’s cousin, Nick Carraway (Maguire), serving as retrospective narrator – one part persecutor, two parts participant – what unfolds is at once a tragic love story and the quintessential dissection of the American Dream.

Yet despite a continued trajectory of US opulence having left the story’s thematic relevance largely undiminished, there has been a certain amount of apprehension about Luhrmann’s ability to retain the book’s strong sense of setting. CGI assisted camera zooms? Rap tracks on the soundtrack? Romeo + Juliet (1996) may have withstood a full Luhrmannisation – modern setting, modern style – but Fitzgerald’s text is different, the spirit of the Roaring Twenties serving not only as a backdrop, but as a character in its own right. The New York of The Great Gatsby should be a city on the crest of a wave; a place where the jazz blares louder, the lights shine brighter, and – in spite of prohibition – alcohol fills almost every glass. To borrow from Nick’s narration, it’s a place where “anything could happen, anything at all.”

Luhrmann embraces the challenge with vigour. With Nick’s narration commenting early that “the tempo of the city approached hysteria,” the film is quick to match the pace. As the audience join Nick as newcomers to Long Island, the opening thirty minutes race us from one character meeting to another – lunch with Tom and Daisy, an encounter with Myrtle, and soon a raucous gathering in a New York apartment where the drink flows and the women flash. With such a lightning fast introduction, it’s easy to feel a jolt, but by the time we find ourselves at our first of Gatsby’s parties, the sheer force of Luhrmann’s style has won. As the crowds queue impatiently through the mansion doorway, light and colour bursting forth, the twirls of a feather-clad dancer beckon us inside; the spectacle has become just as alluring to us as New York has to Nick.

Even the Jay-Z produced soundtrack doesn’t feel out of place. With Luhrmann ever a firm believer that the scores for his period set films should evoke the same feeling in the audience as contemporary music would have done for the characters, bass driven hip-hop may not be historically accurate, but couple it with flapper girls dancing The Charleston and it becomes hard to deny the party atmosphere. Musical purists shouldn’t feel completely hard done by, however – there are also some impeccably handled segues into more traditional fare, particularly during Gatsby’s Gershwin and firework backed ‘Eureka!’ of an introduction.

Yet with such boldness on show, there’s little surprise that the film tends to struggle with some of Fitzgerald’s more nuanced touches. It’s not the cast who are at fault; the performances are almost uniformly excellent, particularly Edgerton as the proud and suspicious Tom, Fisher – all pushed-up bosoms, exaggerated hip sways and coarse New York accent – as Myrtle, and DiCaprio as Gatsby, lending the character a pain behind the eyes balanced only by his near child-like naivety. Where the does film fall down, though, lies with its tendency to tell, when it should only show. A billboard for a now forgotten optometrist is important in the book because it resembles the eyes of God, not because we are repeatedly told it is such. Similarly, Gatsby’s downfall should be a blow that hits us in the moment of its occurrence, not one that we know is coming more than a minute beforehand. As the film draws to a close, the action dials down, making the emphasis on Nick’s narration all the more prominent, his words often appearing before us as floating, 3D type face. Strangely, it is in these moments – those overtly devoted to Fitzgerald’s text – that Luhrmann falters most. This is a director whose best work comes through audacity, not subtlety. Take away the megaphone and you’re left with a man trying to shout, instead of simply amplify.

Recent Comments