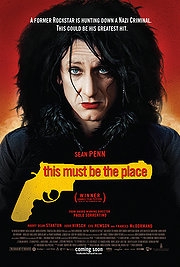

This Must Be The Place

Cheyenne (Sean Penn) used to be an 80’s goth-pop megastar. But now it’s now and he’s moping around his giant mansion in Ireland in full goth threads and makeup, terrifying children and speaking with a sleepy helium-whine. There are other characters, some of whom are likeable – Frances McDormand’s doting wife, Sam Keeley’s lovesick waiter – but don’t worry, they all disappear as Cheyenne is forced to fly to America to look at his dad’s still-fresh corpse.

They never got on, what with Cheyenne being a horribly embarrassing man to know. But a meeting with Judd Hirsch reveals that Holocaust-Survivor Daddy was obsessed with hunting down an Auschwitz guard who’s in hiding. Being dead he’s had to let all that go, so Cheyenne decides to pick up the case, borrowing a stranger’s car and.. err.. driving directly to the place where Daddy knew he was hiding all along. Allowing for how ludicrously untaxing this mission is, Cheyenne decides to faff about a bit on the way.

If you haven’t guessed by the passive-aggressive synopsis, This Must Be The Place is easy to dislike. Taking the ‘Tortured Outcast Road Trip’ blueprint that TransAmerica did much better and running it right through the Metaphometer and the Kook-a-Tron, the result is an infuriating character moving slowly through a distracted narrative, constructed out of events with little-to-no connection and less-to-fuck-all meaning.

There’s a five-minute, single-shot of David Byrne performing the song the film is named after, featuring a 60’s living room set that turns upside down and moves over the heads of the suspiciously young and enthusiastic crowd, before we pan to Cheyenne looking glum. Why? Later, Cheyenne arrives at the Nazi’s cabin. Except he’s not there. He steps outside, and there’s a buffalo. It looks at him. He looks back. End scene. Why? WHY WAS THERE A COCKARSING BUFFALO?

Don’t get us wrong; we don’t need everything explained to us. In fact, the horrific moments of exposition are just as infuriating. In David Byrne’s other scene – he appears as himself and no, Cheyenne doesn’t know why they’re friends either – he watches as Cheyenne explains his entire motivation, stopping just short of bullet pointing the whole thing and taking questions. You’re sad because two kids killed themselves after listening to your lyrics? We know. There was that scene where you visited those graves and two Grieving-Parent-Looking motherfuckers asked you to leave; we remember because we were so excited by something that might actually contribute to a narrative.

Thankfully, this team are too talented to produce a complete turkey, though no-one brought their A-Game. Penn’s fine, doing an impression of Emo Philips meets what-people-assume-Robert-Smith-is-like, but brings nothing of the weight we expect. Many charming performances pepper the first act, but this irritates when it turns out that almost none of those thirty minutes have any bearing on the following eighty. David Byrne (him again) and Bonnie Prince Billy’s soundtrack is pretty enough, until you realise how good a Remain in Light/I See a Darkness mash-up would be and burst into tears.

And there are giggles, sure. The only time the unbearable slowness of Cheyenne has any value are the flashes of Penn’s brilliant comic timing, and McDormand goes full Fargo for her extended cameo. But just as many laughs fall flat; the whole gag for Harry Dean Stanton’s scene is that he invented the wheelie suitcase. Oh Lord, hold onto your sides.

But people will love this film. They’ll love it like they love anything self-consciously weird. They’ll somehow relate to Cheyenne, rather than rationally wanting to slap him ’til he stops acting like a Vitamin D-deprived toddler. They’ll even find meaning in the ending, wherein Cheyenne does something bizarre and faintly psychotic, then undergoes the most rapid last minute character development since Dr. Everett Scott’s fishnets. But let it be known; they are wrong.

Recent Comments