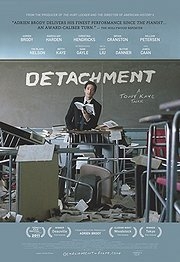

Detachment

They fuck you up, your mum and dad, They don’t mean to, but they do. Oh Phillip Larkin, how eloquently you sum up the universal crisis of the youth of humankind. A sentiment that is also at the heart of Tony Kaye’s Detachment, with a side note that they also fuck up your teachers and are directly responsible for failings in the public school sector.

Having dealt with neo-Nazi racism in American History X and abortion in Lake of Fire, Kaye turns his attention to the education system. Set in a high school in Mineola, Long Island, but representing every high school in America, this stylized indie piece explores a month in the life of Henry Barthes (played beautifully by a forlorn Adrien Brody). Choosing life as a substitute teacher, preferring to never stay long enough to forge any real emotional connections, Henry finds himself in a public school filled with world-weary teachers (including Marcia Gay Harden, Christina Hendricks and Lucy Liu) and an apathetic and violent student body.

It’s not immediately apparent that this is just another inner-city school and not a refuge for total delinquents – at one point a child puts a cat in a rucksack and punches it to death – but we gradually establish that these are supposed to be a representation of normal kids, failed by the system, their parents, the state.

Henry forms an attachment to three very different women: fellow teacher Sarah (Christina Hendricks), chubby, misunderstood artsy pupil Meredith (played superbly by the director’s own daughter Betty Kaye) who develops a schoolgirl crush on him and runaway teenage prostitute Erica (newcomer Sami Gayle) who he meets on a bus and lets follow him home. None of these relationships, despite their power and potential, develop as part of the plot. This isn’t the story of a disillusioned high school teacher who gets his life back on track through caring for a child prostitute, or manages to change the lives of his violent pupils through winning the state choir competition, or even finds ill-fated love with another teacher. Infact it’s not really a story at all. Detachment is an exploration into the vicious cycle of poor parenting, with Henry’s own terrible experience with his mother hinted at throughout and eventually revealed to explain his lifestyle choice.

Where this exploration falls down is in ramming the parental damage home at every turn – this child abandoned, that child called fat – until all that misery becomes a little hard to swallow. In one particularly unbelievable sequence, the teachers all wait alone in their tidy classrooms on parents’ evening and no one shows up. Maybe there was an administrative error, you cry, surely not every parent of every child in the school doesn’t give a shit. Surely it can’t be so black and white as parents equal evil, teachers equal forces of good (that said, it does make you want to get in touch with the teachers you never thanked, and the few you never apologized to, which is something we should all do).

Detachment, Tony Kaye will tell you, is ‘about being a parent…family is everything’ which is interesting because he walked out on his family when his girls were two and five. He cast his own daughter here but will happily tell you that he would have ‘risked her not talking [to him] for years’ if someone better had turned up to auditions. Yes Tony, that’s great parenting.

Following the release of American History X in 1998, Kaye entered into a lengthy battle with its star Edward Norton, the production company New Line Cinema and the DGA over creative control, and followed that by spending nearly a decade in the film-making wilderness. Nobody wanted to make films with him, which you can sort of understand given that when the DGA wouldn’t let him remove his name from the New Line edited version of American History X, he insisted it be credited to Humpty Dumpty and filed a $200 million lawsuit when they refused.

Heralding his return to feature films, Detachment is not as powerful as it could or should be. Visually, the film is impressive and well-executed, full of shifting shots, extreme close-ups, animated chalkboard graphics and home-video flashbacks, but it’s so preoccupied with shouting ‘Blame the Parents’ and throwing everyone’s respective (and largely parent-based) depression in our faces that we can’t take it seriously.

The exceptionally talented cast are all superb, particularly Brody, but the script isn’t strong enough to justify everyone being so bitterly unhappy. Some excellent performances get lost in an onslaught of self-pity you simply can’t believe in. The problems of the public school system are very real but they’re not nearly so one-dimensional as Detachment wants you to believe. Sure, they fuck you up, but they’ve got some redeeming features, those parents of yours and they’re not single-handedly responsible for the declining education system.

Recent Comments