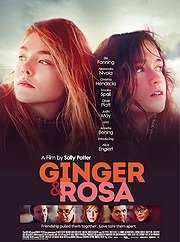

Ginger & Rosa

Ginger & Rosa opens with a shot of a mushroom cloud. It’s appropriate, given that the threat of nuclear war hangs over the entire film, and, particularly, main character Ginger. Ginger and Rosa are lifelong best friends – they were born at the same time, while their mothers held hands – and spend every waking moment together. Most of this is conveyed in a short sequence at the beginning of the film, which brings us up to London, 1962, where both girls are seventeen and struggling to cope with their fractured home lives and a world that’s simultaneously metamorphosing into something new and tearing itself apart at the same time. Much like the girls themselves.

We’re led to believe that Ginger and Rosa are inseparable, but having not seen much evidence of anything but a superficial connection, it’s difficult to invest in them when their life paths begin to diverge. Ginger is terrified of ending up a domestic housewife like her mother, and constantly preoccupied by the looming atom bomb. She reacts against both, moving in with her smug, free-spirited father and joining up with the CND movement (Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament). Rosa, meanwhile, turns to religion and boys. Or, rather, men.

The principal problem with Ginger & Rosa is that nearly everyone in the film is a dick. That’s not to say that the performances are bad – they’re generally pretty good – just that the script has populated the film with characters you’ll hate. Whether this is intentional or not is irrelevant when the result is that it renders the film almost impossible to watch. Ginger fancies herself as enlightened; an intellectual and a poet (NOT a poetess), and yet she lashes out at her mother for… what, exactly? For trying to provide her with a loving home? For giving up on her painting career to care for her? For generally being a great mum? She’s the sort of dreadfully precocious creature that answers the question “Where have you been?” with inane utterances like “Oh, just roving about. Being free”. Oh, do fuck off Ginger. She’s the sort of girl who floats around doing cartwheels, just because. “I’d rather the world didn’t end tomorrow. Wouldn’t you?” Not with lines like that.

Newcomer Alice Englert’s Rosa is given far less screen-time, but is no less irritating. It’s not the girls’ fault they’re awful; Rosa’s absent family, and Ginger’s broken one, haven’t given them much in the way of role-models. They’re so keen to act like adults, but they don’t really know how. Alessandro Nivolo (one of an inexplicable number of Americans in the cast of a distinctly British film) gives a good performance as Ginger’s father, but is lumbered with an excruciating arse of a character. His Roland is a bohemian bastard, preaching love and peace, yet causing nothing but hate and friction in the lives of his daughter and wife. He’s the sort of person who names his daughter Africa (Ginger is just an understandable nickname). When Rosa is swept up in his smug-storm, she wants to “fix him”, and he starts blathering on about how this seventeen year old child is his soul mate. It’s intensely uncomfortable, both for the audience, and for poor Ginger.

Elle Fanning is largely good as the fiery-haired lead, despite the inherent awfulness of the character, and achieves a very passable British accent, even if she does have a tendency towards an overly-mannered delivery. While much of the film is intolerable, the story-thread that focuses on the effects of Rosa and Roland’s betrayal of Ginger are terrific, and Fanning plays the hell out of those scenes – particularly the climactic confrontation. The emotional displacement that Ginger puts into the CND movement may be wearisome – her childish politics masking the emotional bomb she’s really worried about – but the source of her trauma is well played and devastating.

Stranded among the roster of risible quasi-hipsters, Christina Hendricks’ character is a nice counter-part to her Joan Holloway in Mad Men, and could be a saving grace, were it not for her complete inability to do a British accent. Hendricks’ acting is fine, but the accent is all over the place, and renders any scene with her an unfortunate chore. (Why on Earth they didn’t just cast British actors is baffling.) Thank god, then, for Timothy Spall and Oliver Platt. Their gay couple – a trait which is thankfully and uncharacteristically subtle – are the only sane voices, able to cut through the bullshit of all the other characters and actually get through to Ginger, and subsequently the audience. “Ginger, my darling, can’t you just be a girl for just a few moments longer? You’ll be a woman soon enough”.

The film is nicely shot, with director/writer Sally Potter doing a much better job behind the camera than with the pen, and while it looks a little Instagrammy, the soft-focus cinematography depicts the era nicely. The soundtrack, too, is appropriate, ruled over by Dave Brubeck’s Take Five (although Ginger’s predilection for jazz doesn’t help soften the cloud of pretension that suffocates the film.)

Ginger & Rosa has a great cast, and some beautifully framed images, but with a cast of characters that are almost universally detestable, it’s difficult to care about anything that happens to them. That moments of genuine heart do shine through is almost entirely down to Elle Fanning, who displays moments of extraordinarily raw emotion amid the pretentious nonsense. A better script, and this could have had more going for it than Fanning’s portrayal a young girl’s suffering. As it stands, it’s mostly just insufferable.

Recent Comments