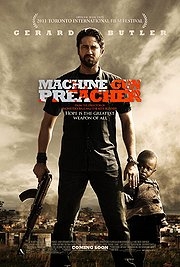

Machine Gun Preacher

The title of Machine Gun Preacher tells you pretty much all you need to know. Only, wait – Sam Childers is not a preacher. Not in the ordained sense, anyway. He builds a church in his Pennsylvania home town and preaches to – or yells at – those who attend, but it’s only the orphaned children of Sudan who refer to him as “the white preacher”. Yes, Marc Forster’s latest film manages to be even more racially insensitive than The Kite Runner, shamelessly idealising Childers as the self-sacrificing saviour of truckloads of African children.

Despite taking place largely in Africa, Machine Gun Preacher is probably the most Middle American film you’ll ever clap eyes on. Sam Childers (Butler) turns from druggie biker ex-con to religious savant after almost (but not actually) murdering a hijacker, taking this generation’s token weirdo Michael Shannon with him to the righteous side and setting up a cosy new home in the woods with his wife (Monaghan) and daughter (Madeline Carroll). But a visiting speaker from the African mission inspires Sam to head over to Sudan and save all the children. He does this by building an orphanage and killing all the faceless evildoers trying to stop him. So far, so inspiring.

In true Christian fashion, Sam is redeemed by a quick dunk in some holy water, and immediately becomes the family man, a strong and protective community leader. He’s alternately framed as an action hero, holding an impenetrable stance in the middle of the road like Jean Claude Van Damme, or as a Christian saviour, the camera zooming out from his bricklaying to frame him inside the crucifix he’s building. Asche & Spencer’s soundtracks runs through the entire spectrum of inspirational instrumentation to signify Sam’s mystical heroism – the kids, he’s told, believe he’s protected from bullets by angels. But those kids only come in shepherded, petrified flocks, gathered in crevices or the back of trucks. Only one, William (Junior Magale), whose tragic story is told in the macabre pre-credits sequence, is given a distinct identity, and even then it’s only that of a silenced boy who follows Sam around like a lost puppy.

Machine Gun Preacher is based on a true story, so be careful what you say or Childers might jump out of the screen and ask why you paid to see it rather than giving him the money to save some more orphans. There’s inevitably going to be a side of guilt served up with any film along these lines, but ultimately this is – or ought to be – entertainment, not a public service announcement. However, it becomes obvious pretty quickly that everyone involved here is besotted with Childers (Butler also served as an executive producer, so you know he really cares).

Forster’s wide compositions keep Sam at the arm’s length such deification requires, simultaneously disengaging from the emotional plight of any of the children or people around Sam. Butler’s colourless performance doesn’t help dig any deeper, either. The two modes of his career – burly, yelling action man and gruff but sensitive leading man – are both in evidence, hemmed in by a wavering accent and a ragged script. His growly yelling (sorry, no, he never says “Sparta!”) does at least make more of an impact than the ‘genial hero’ model where Sam becomes impervious to negativity and Butler becomes eerily vacant.

Machine Gun Preacher is a film disconcertingly dedicated to worshipping one man, insisting that even his dark criminal past is worthwhile, a vital aid in his heroic ventures. But this deification of a white saviour in a foreign land is not exactly what you’d hope modern Hollywood would be preaching. Gun them down.

Recent Comments